Women in the 1868 General Election

The 1868 Campaign to Put Women’s Names on the Electoral Register in Leeds

The Reform Act 1867 was so hastily drafted that its legal implications on several points were unclear.

Terms used in parliamentary legislation were clarified in 1850. The regulations now specified that the term “man” should be held to incorporate women – as in “mankind”. Where the legislative intention was gender specific, “male person” must be used.

The Reform Act 1867 used “man” throughout.

During the parliamentary debates, John Stuart Mill moved an amendment substituting “person” for “man” throughout the proposed legislation. He was defeated by 196 votes to 73. Both MPs for Leeds voted in favour.

The Reform Act gave the borough or urban vote to all rate paying male householders to male tenants in lodgings worth b>at least £10 per year who had been resident in the town for at least 12 months. This effectively doubled the voting population in seats like Leeds.

The Reform Act also required that the rates must be paid to the Council in person. Tenants could no longer “compound” or include their rates with the rent paid to the landlord if they wished to vote. This proved very unpopular. Male tenants across the country had to appear before the local Revising Magistrate to agree the value of their rent without the rates element and then establish whether the rental value alone qualified them to vote.

A new Register of Voters had to be compiled in line with the Reform Act’s complex criteria. The registration procedure involved the local Overseers of the Poor publishing a list of potential voters. Anyone who thought their name had been excluded or thought someone else’s name was included by mistake had to make formal representations to the Revising Magistrate. The Conservative and Liberal parties both sent barristers to all the hearings to represent their local interests.

The Manchester Women’s Suffrage Society launched a campaign for qualified single women and widows to register as voters.

In Leeds, 23 women volunteered. The names of 22 are unknown but one of them was probably Constance Holland. They were supported by the local Liberal party. Their claims were heard on Friday 18 September 1868.

Mary Howells

The newly appointed Revising Barrister for the West Riding was Thomas Campbell Foster. The first claim he heard was that of a Quaker widow, Mary Howells. She gave her address as 1 St Alban Place, Wade Lane, Leeds. This area was demolished and redeveloped in the 1970s.

Photograph taken immediately prior to demolition

Image courtesy of Leeds Library & Information Services

Mary Howells was 66 and gave her employment as “Sewing machine operator employing two assistants”.

Thomas Campbell Foster spoke at length on the interpretation of the law. The Reform Act 1832 stated that ‘the franchise was given to “every male person”,’ he said, ‘clearly excluding female persons.’

He continued to the laughter of the courtroom: ‘If entitled to vote, why should ladies not be entitled to sit as Members? Their wisdom and eloquence might be of great advantage. Why might they not be in the Ministry? Why not Chancellor of the Exchequer or Prime Minister? It would be turning out constitution into ridicule if our Lady Chancellor, bringing forth her financial statement, announced she had just been confined of a fine boy.”

Image courtesy of Leeds Library and Information Services

He concluded: ‘I presume ladies desire to be in the same position as men. Now, men who put forward frivolous claims are liable to pay costs. I think the course the claimant before me has taken is ill-advised and ill-judged and I must therefore order her to pay 10s costs.’

Mary Howells replied: “When the law is administered, it should be done by sensible remarks” and left the Court. The other 22 women had no option but to withdraw their cases.

The claimants due to appear before Mr Campbell Foster at Batley and Dewsbury also withdrew their claims.

The local and national press condemned Mr Campbell Foster’s behaviour and praised Mrs Howells for her dignity. However, their objections were only based upon his lack of courtesy to a lady; they all agreed with his interpretation of the law.

Lawyers and politicians argued that women were denied legal rights because men wanted to protect them from unpleasantness. Women who challenged the status quo were viewed as voluntarily rejecting male protection, implicitly making themselves vulnerable to male violence. Having a vote bestowed civic responsibility on a man but debased a woman; involvement in the rough and tumble of politics would rob her of her feminine delicacy and refinement.

In Manchester 13 women succeeded in registering as voters. At the next general election, 9 of them voted.

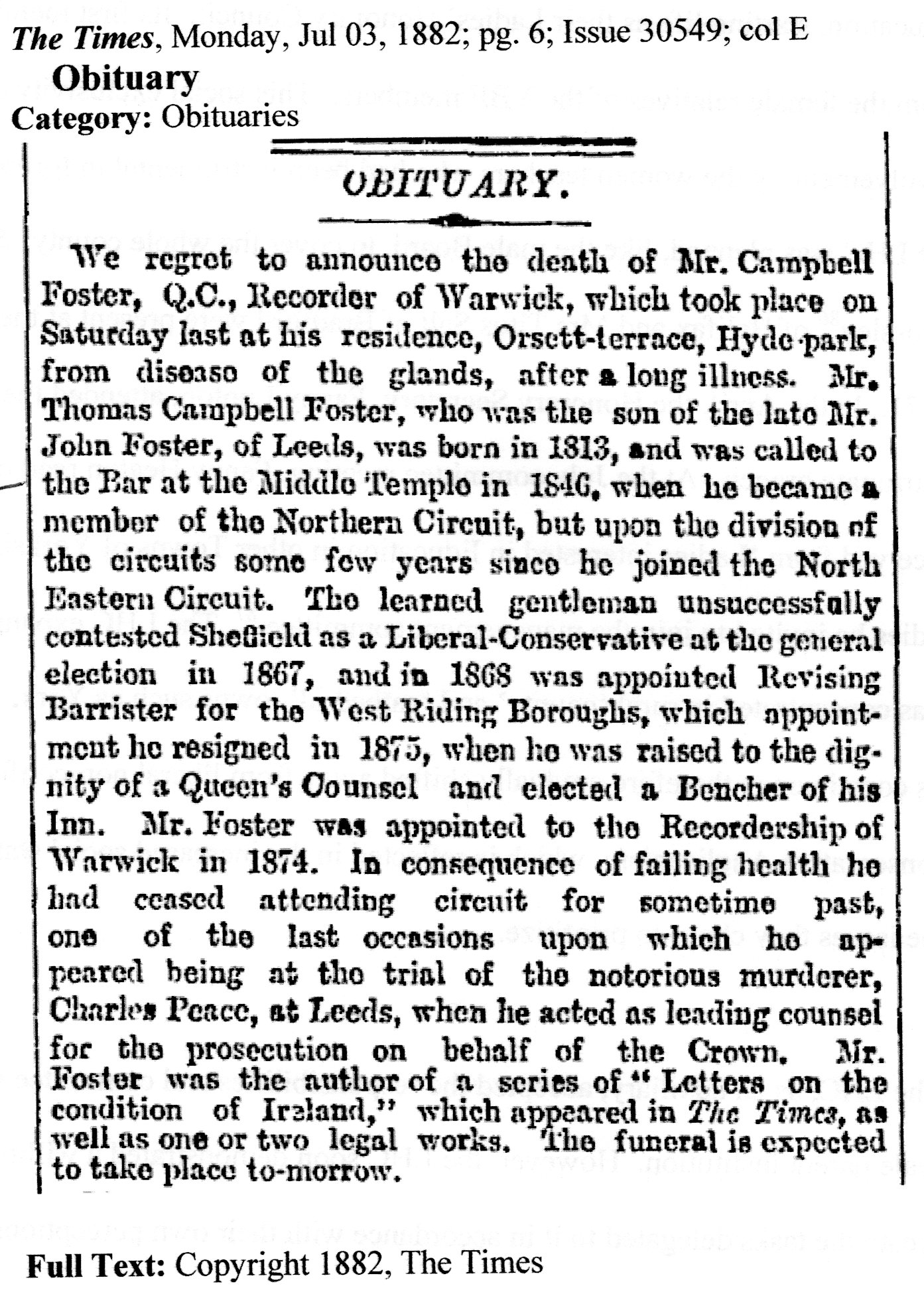

Thomas Campbell Foster Q.C.

According to his Dictionary of National Biography entry, which is based almost entirely on the (same) obituary to appear in the Times and the Leeds Mercury, Thomas Campbell Foster was born in Knaresborough on 6 October 1813. His father was John Foster, a printer. In December 1828, John Foster took over the Conservative Leeds Patriot newspaper and the family moved to Leeds. Under Foster, the paper opposed the 1832 Reform Act and the 1834 Poor Law Act, but supported Richard the movement for factory reform.

Thomas Campbell Foster was admitted to the Middle Temple on 23 April 1840. However, he was not called to the Bar (i.e. qualified to practice as a barrister) until 1846.

Instead he began a fairly successful career in journalism, starting as a sub-editor in Liverpool before being sent to South Wales as a special correspondent for the Times to report on an attack on the Rebecca Riots, so called because the insurgents dressed in women’s clothing to attack the newly installed toll gates. On 19 June 1843, Carmarthen workhouse was ransacked and torched while the dragoons sent in to restore order were encouraged by an officer to ‘slash away’ at the crowd.

Campbell Foster remained in Wales for 6 months. He travelled around West Wales where the insurgency was particularly prevalent, talking to the people. He reported daily on the local economic and social conditions and upon the grievances behind the Riots. He gained the trust of the Rebecca-ites and was permitted to attend some of their secret meetings as well as the large hillside gatherings of their supporters. His sympathetic reports ‘revelled in the embarrassment of the authorities.’

The Times then sent him to report on an outbreak of incendiarism in Norfolk and Suffolk. He established himself as their expert on rural unrest and social conditions. Then in 1845 he was sent to Ireland. His trenchant attacks on Irish landlords and particularly upon the Irish hero, Daniel O’Connell, caused much controversy. Perhaps this is why he abandoned journalism in 1846 and returned to the law.

Campbell Foster had red hair and it seems he possessed the short temper stereotypically associated with this. According to the Leeds Mercury of 24 July 1852, he put his opinions of another barrister’s politics in a letter to a colleague. This colleague published the letter and the other barrister, Digby Seymour, took offence. The incident culminated when:

‘The parties met in the robing room at York Castle, and after some words, Mr Foster who had a cane in his hand, struck Mr Seymour three or four smart blows across the shoulders. Mr Seymour resented this violence and a “set to” commenced in the course of which both the “Learned Gentlemen” came to the ground…other barristers who were present then interposed.

The judges summoned Mr Foster and Mr Seymour before them in their private rooms [where] they were required to enter into their own recognizances in £500 each to be of good behaviour to each other for the next six months.

The “Learned Gentlemen” were also admonished on the great impropriety of their conduct.’

Leeds Mercury, 24 July 1852

Despite this incident, Campbell Foster built up a large practice in Leeds. He took on cases from obstruction of the highway to fraud, rape and murder. Five years after the robing room incident, he was being spoken off as a possible Recorder of Leeds.

His most famous trials were that of Mary Ann Cotton in 1873 and Charles Peace in 1879.

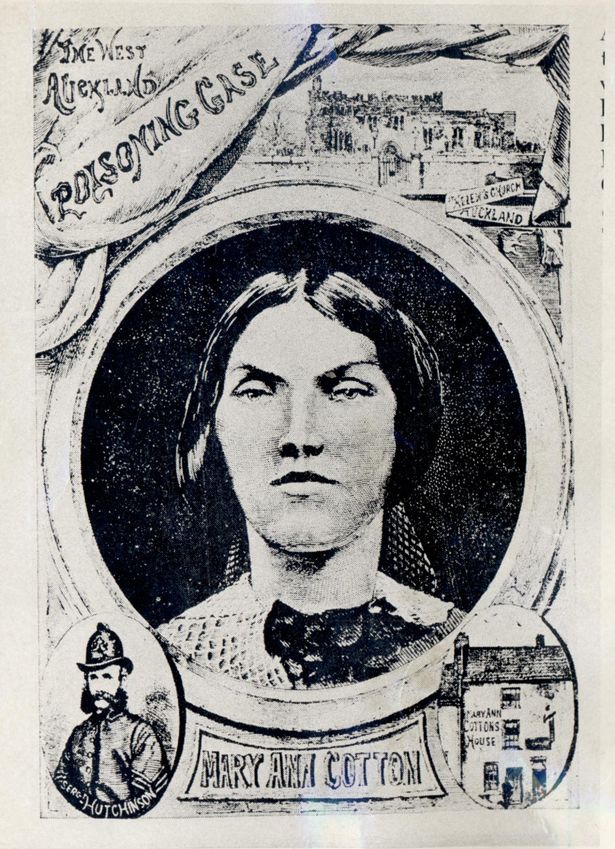

Mary Ann Cotton was suspected of killing up to 21 people but only tried for the murder of her stepson, Charles Cotton, after the West Auckland workhouse refused to admit him.

Campbell Foster was appointed as her defence counsel after her original barrister ran away with her money. Her defence was that the boy had died after accidently inhaling arsenic from his bedroom wallpaper (arsenic was popularly used to kill bed bugs and similar infestations).

However, the Judge allowed the prosecution to bring evidence of four previous poisonings with which she had originally been charged; those of her (bigamous) husband, Frederick Cotton; another stepson; her 10-month-old baby; and her lodger and lover, Joseph Natrass. The bodies of all five victims were exhumed and autopsies conducted by Dr Thomas Scattergood, lecturer in forensic medicine and toxology at Leeds Medical School.

Mary Ann Cotton was found guilty and executed at Durham Gaol.

On 4 February 1879, Campbell Foster was the leading prosecutor in the case against Charles Peace, the Sheffield burglar and murderer. The trial lasted one day and the jury took only 10 minutes to find Peace guilty.

Interesting trivia about this trial include:

Peace’s solicitor was William Clegg, a former football player for Sheffield Wednesday and England

Peace is mentioned by name in The Case of the Illustrious Client by Arthur Conan Doyle

This was one of Campbell Foster’s last Court appearances; he was already suffering “failing health”. He died at his London home on 1 July 1882. He left a widow, Isabella, an estate of £18,248 10s 4d and a 10 guinea prize for achievements in the Bar examinations.

Mr. Campbell Foster at Leeds

Taken from The Englishwoman’s Review 1 October 1868

Mr T Campbell Foster has been guilty of very unmannerly conduct. In his brief authority as Revising Magistrate at Leeds he has condemned the claim of women to the franchise as “frivolous, groundless and absurd” and has inflicted a fine of ten shillings on a lady making it. This is hard treatment.

It may, in Mr Campbell Foster’s opinion, an ill-advised thing for women to claim the franchise at all; but, at the present moment such a claim cannot be justly stigmatised as frivolous and absurd. The appearance of the names of many thousands of ladies on the overseers’ lists in various parts of the kingdom

From the Daily News

Revising Barristers are empowered to allow costs to voters frivolously objected to, and those costs go to the person so annoyed; but we believe no barrister can mulct a claimant; certainly the penalty cannot be enforced, and no destination is provided for the money if it is paid.

The proceeding was contrary to all precedent, and, if it had not been condemned by the Barrister’s virtual acknowledgement of the importance of the question, would have been sufficiently discredited by the fact that elsewhere cases have been granted on the point.

From the Star

Having determined to dismiss the claim, Mr Foster Campbell would have done so with a better grace if he had limited his remarks to a simple statement of his legal opinion; and his fancies were in miserable taste both in point of gallantry and of judicial dignity. But the Leeds barrister added injury to insult; he termed the claim of Mrs Howell frivolous, and sentenced her to pay 10s costs! This must be emphatically condemned as absurd and oppressive. If the same measure had been meted out to men, claiming or objecting, many would have been mulcted in half-sovereigns.

From the Telegraph

At Leeds however courtesy failed. Mr Foster Campbell, the revising magistrate, used very uncivil language towards a highly respectable Quaker lady, Mrs Howell, and actually finer her ten shillings for making what he called a “frivolous claim.”

His conduct excited the indignation even of persons who are opposed to giving the suffrage to women, and has been very properly commented upon by the newspapers.

From the Leeds Mercury

Mr Foster Campbell Obituary

Jacob Bright

The Municipal Franchise Act 1869

Jacob Bright, MP for Rochdale, was leader of the pro-women’s suffrage group in the House of Commons.

The Municipal Franchise Act 1869 was designed to bring the franchise in the towns into line with the parliamentary franchise as amended by the Reform Act 1867.

Bright’s amendment changed “man” to “person” throughout the new legislation. He argued that this merely restored the right to vote in local elections which had been removed in 1835.

From 1870, unmarried women and widows were able to vote in all local elections including for Poor Law Guardians and the School Boards.

Opposition to Women's Rights

There was no formal organised opposition to women’s rights or women’s suffrage until 1908. This was because the majority accepted that women were weaker, less intelligent and generally inferior to men. The medical profession confirmed that physical and intellectual activity damaged a woman’s capacity to have children.

The repeal of tax on paper, new print technology and increased literacy meant there was a huge audience for newspapers and new illustrated magazines such as Punch and Vanity Fair.

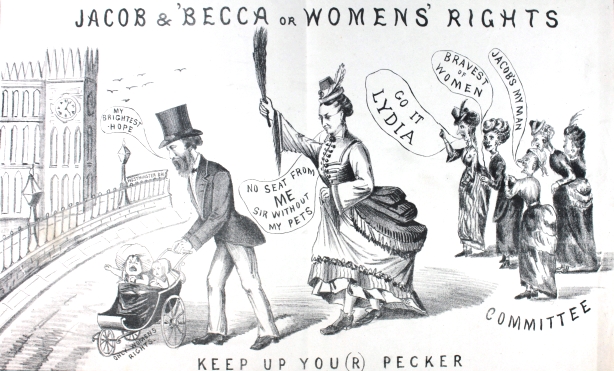

The caricature below shows Jacob Bright, leader of the pro-women’s suffrage group in the House of Commons and Lydia Becker, secretary of the Manchester Women’s Suffrage Society.

There is a long history of portraying women who challenge the status-quo as ugly, deformed, desperate creatures and of portraying the men who support them as emasculated or deviant.

The lack of beauty and femininity in the suffrage committee is designed as warning about the threat to the established social order; the “Becca” in the title is a reference to the Rebecca Riots in the 1840s when rioters dressed as women while destroying property.

Jacob Bright’s unmanliness is demonstrated by his pushing a pram. Lydia Becker meanwhile wields a birch switch and lifts her skirts to reveal her ankles; this and the exhortation beneath the image underline the slander that they share an illicit sexual relationship in which his performance depends on flagellation.

Punch, 5 May 1866