Women Poor Law Guardians 1883 - 1903

Leeds Workhouse in the 1860s

“Let no-one be deceived into imagining [being a Poor Law Guardian] is a dilettante occupation or a harmless hobby for a few hours of leisure; let anyone who will do it, do it well and let her understand that means doing it by hard, persistent, thorough work…but work which I, at least, have found practicable, honourable and rewarding.”

Gertrude Wilson, Leeds Poor Law Guardian 1885-1893

at the National Union of Women Workers Conference held in Leeds 1893

Women Poor Law Guardians, 1883 to 1903

| 1883-1884 |

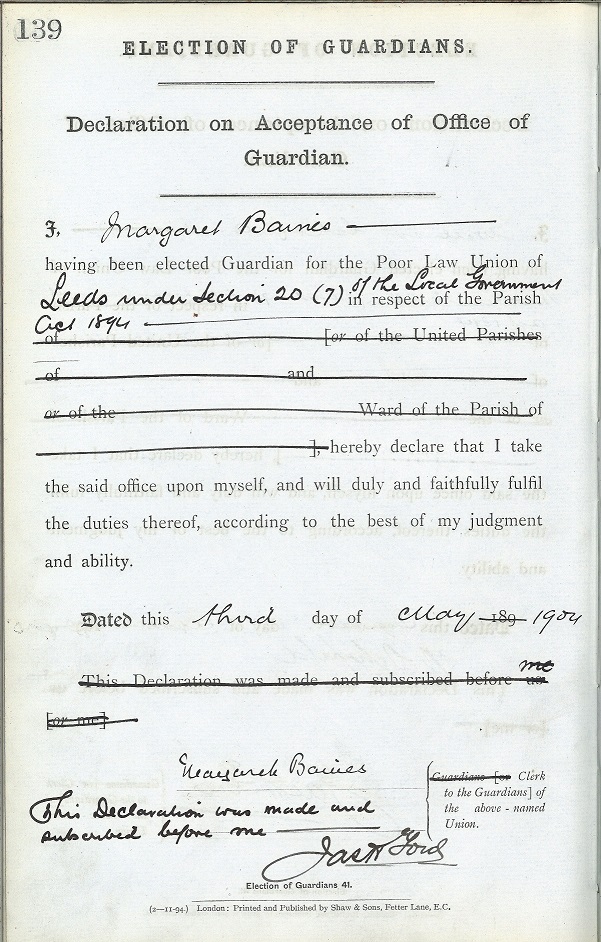

Louisa Carbutt, Westfield Grove, St Michael’s Road, Headingley – elected on the Liberal ticket for Headingley-cum-Burley ward. Miss Carbutt married mid-1884 and left Leeds. The Board of Guardians co-opted Margaret Baines, Shire Oak Road, Headingley, to fill the vacancy. |

| 1884-1888 | Margaret Baines was elected on the Liberal ticket together with Gertrude Wilson, 6 Montpelier Terrace, Lower Headingley |

| 1889-1891 | Margaret Baines and Gertrude Wilson re-elected. Margaret Baines comes head of the poll |

| 1892-1894 | Margaret Baines and Gertrude Wilson re-elected. Margaret Baines again comes head of the poll |

| 1894 | Local Government Act abolishes the property qualification for Poor Law Guardians and extends the local franchise to married women who own property separately from their husband. |

| 1895-1897 | West Ward:

|

| 1898-1900 | Margaret Baines for Headingley-cum-Burley ward Eliza Dickenson for Rothwell ward |

| 1901-1903 | Leeds:

|

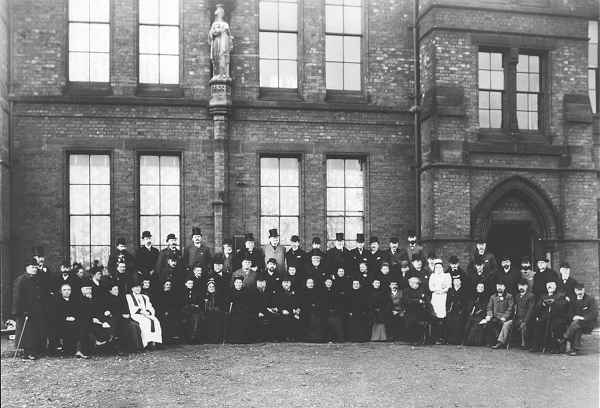

A GROUP PHOTOGRAPH OF THE GUARDIANS OF THE POOR OF THE LEEDS UNION TAKEN OUTSIDE THE WORKHOUSE (NOW THE THACKRAY MEDICAL MUSEUM) IN THE 1890s

The photograph was possibly taken to celebrate the opening of the new Nurses’ Home in 1896.

It was no longer acceptable to use able-bodied inmates as nursing staff. Professional nurses preferred to work in voluntary hospitals which offered a greater variety of experience and better salaries. The Guardians hoped to overcome the skills shortage by training their own nurses.

The removal of the pauper children to smaller “scattered” homes with foster parents from 1895 left the industrial school buildings available for conversion to hospital wards. They were re-opened in 1906 as Lincoln Wing.

The photograph is of the “Leeds Guardians and their ladies” so, unfortunately, it is impossible to identify the women Guardians amongst the crowd.

The Field For Women Guardians

A paper was read on “Women in Local Government”. Owing to the removal of the marriage and rate-paying disqualifications, many women of leisure could now become Guardians, and bring to their work that practical knowledge of the care of the poor which almost every woman with heart and head possessed.

While women Guardians were in favour of severe discipline for able-bodied paupers, they would remove the stigma of pauperism from the innocent children by boarding them out. Workhouse children had not even a piece of string they could call their own. Women Guardians should advocate the employment of paid women inspectors for children and lunatics, and they would be able to look into matters quite beyond the province of men.

Women as Guardians had special qualifications. They brought practical experience to the work. Many of the Guardians were tradesmen and tried to promote the interests of a clique, while women sat supremely apart and judged the case on its own merits.

On a Board composed exclusively of men, they had spent an hour discussing the matter of buttons versus hooks-&-eyes, which the dressmaker eventually decided for herself.

from Leeds Mercury 25 October 1894 "The Conference of Women Workers"

Before 1894, Guardians had to own property worth £15 homes. The Local Government Act 1894 abolished the property qualification so any ratepayer could stand for election as a Guardian, regardless of gender or marital status.

Compare the picture of Headingley in 1900, on the left, where Louisa Carbutt, Margaret Baines and Gertrude Wilson had homes, with the photograph of Beeston Road in 1897, on the right, where Mary Woodcock lived with her husband, less than half a mile from the Old Hunslet Workhouse on Hillidge Road

Images courtesy of Leeds Library & Information Service

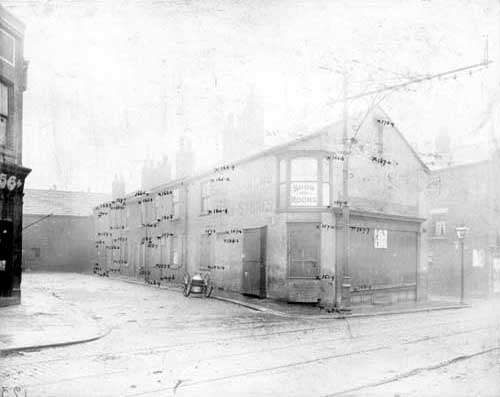

The Leeds Poor Law Guardians Office on East Parade at the junction with Greek Street: this is where applicants for relief had to appear before the Guardians on Wednesday afternoons

The municipal buildings, including the Public Library and School Board offices, are in the background

By the time this photograph was taken in 1938, the building had become the head office of the Guardian Assurance Company

Louisa Carbutt

1832 - 1907

Louisa was born in Altona, near Hamburg. Her father, Robert, originally a Quaker, was a partner in the Pudsey firm of Stansfeld, Brown & Co. Textile Manufacturers. Her mother was a Danish-German Lutheran.

In 1838, the family moved to Paris for two years before returning to Leeds. By this time the family had converted to Unitarianism and worshipped at Mill Hill Chapel. Robert became a Director of the North Midland Railway and entered local politics as a Liberal, rising from Councillor in 1843 to Mayor in 1847. When he died in 1874, his estate was divided equally amongst his seven children.

Unusually for the time, the Carbutts gave their daughters the same standard of education as their sons. They all spoke fluent German, French and Danish. Louisa and her sisters boarded at a school in Hamburg where they studied literature, Latin, mathematics and science, and were introduced to Frobel’s child-centred educational theories.

When the family returned to Leeds, Louisa and her sisters taught at the Mill Hill Sunday School for Adults. By 1858, she had determined to open her own school for girls. Her mother supported this ambition but her father was horrified; he only agreed to the venture when she agreed to open the school away from Leeds - in Knutsford, Cheshire.

The school, Brook House, rapidly gained a reputation for the academic quality of its curriculum. Many Unitarian families in Leeds chose to send their daughters as boarders to study there. Louisa, however, refused to expand beyond a number of pupils she could teach personally. After her death, her husband published a memoir of the school (displayed in the exhibition).

Louisa Carbutt signed the 1866 Women’s Suffrage petition and was an early member of the Manchester National Society for Women’s Suffrage. She attended the Manchester Conference on Women’s Education in 1868, organised by Lydia Becker, where she met Constance Holland.

Unfortunately, she had to close her very successful school in 1870 due to her ill health. Louisa returned to Leeds, eventually moving to Westfield Grove on St Michael’s Road in Headingley with her younger sister.

When her health recovered, Louisa became involved with the Leeds Ladies Educational Association, arranging the Cambridge extension course lectures and examinations for women teachers. She ran a library where the candidates could access books and study. She joined the campaign to open Leeds Girls High School.

In 1875, she opened the Leeds Employment Registry for Governesses. She arranged loans to women teachers deterred from the Oxford and Cambridge examinations by the fees and helped them to find employment. An imbalance between supply and demand for women teachers meant that the Registry always operated at a loss. To Louisa’s disappointment, many of the applicants refused to consider alternative employment suggestions (typewriting, book-keeping, clerking) because of the loss of social status implied in accepting a commercial position.

Like Alice Cliff Scatcherd, Louisa was an energetic and popular public speaker about women’s suffrage across the country. She was involved in the “cottage” meetings arranged by the Leeds Suffrage Society and spoke at several of the Grand Suffrage Demonstrations in the early 1880s, including Bradford and Sheffield.

The Poor Law Act 1834 was unclear as to whether women could stand for election to the Board of Guardians. The eligibility bar was high as candidates needed to own property on which they paid rates of at least £15 per year.

A court ruling in 1875 encouraged a few suitably qualified women to try but they were disqualified by the Returning Officer or actively campaigned against by male candidates.

In Leeds, the local Liberal party were persuaded by their Secretary, Francis Carbutt (Louisa’s brother), to include a woman candidate on their slate for the 1882 elections. Louisa Carbutt was duly elected and took her seat in January 1883. Her first task was to try on forty ulsters (overcoats) for her male colleagues.

“It was in great part through her exertions that our pauper children were clothed like their little brothers and sisters of happier lot, and sent to the Board Schools, instead of being secluded in the workhouse.”

Charles Hargrove, Minister at Mill Hill Chapel

In 1884, Louisa married a fellow teacher, William Herford, and they retired to Paignton where she died in 1907.

The Leeds Liberal party were sufficiently impressed by her work with pauper children during her tenure as a Poor Law Guardian that they co-opted another woman, Margaret Baines, to take her seat.

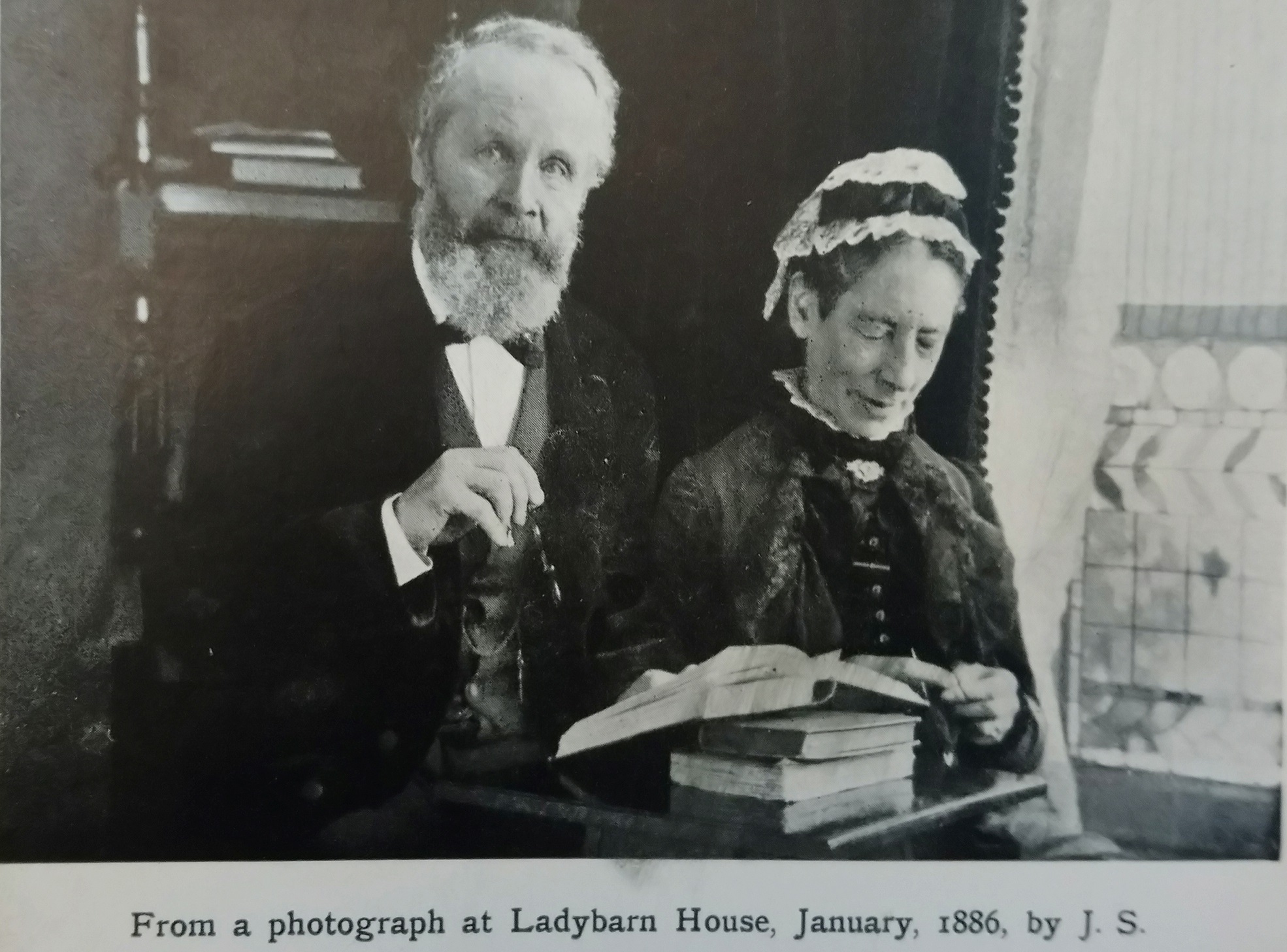

Louisa Carbutt and her Husband William Herford

Guinea Graves at Beckett Street Cemetery, Opposite the Workhouse

Also known as “subscription graves”. This type of burial was introduced in 1857 and continued until 1939. It enabled the poor to give their dead a decent burial, albeit in a communal plot with a shared headstone. The cost of One Guinea (One pound and one shilling) included a commemorative inscription of up to 35 letters.

Margaret Baines

Margaret was the daughter of Edward Baines, owner of the Leeds Mercury, the “foremost Liberal newspaper outside London”, and an MP for Leeds. Her sister, Jane, married Edward Crossley of the Halifax carpet manufacturers and MP for Sowerby.

Margaret Baines had a private income settled on her by her father and moved to Shire Oak Road in Headingley. She was involved with the Yorkshire Ladies Council of Education and other similar philanthropic organisations, taking a particular interest in charities for children.

In 1884, she was co-opted to the Leeds Board of Guardians by the local Liberal Party to replace Louisa Carbutt, who was no longer eligible to serve after her marriage.

At the next election in 1885, Margaret Baines was re-elected for the Liberals with a second woman Guardian, Gertrude Wilson.

Margaret Baines served as a Poor Law Guardian for over twenty years. Many women Guardians used their role to demonstrate female efficiency and fitness for the vote. Margaret Baines wished to distance herself from such political gaols so, from 1888, she stood as a non-political candidate, emphasising the philanthropic nature of the work.

She told a Royal Commission on the Poor Laws in 1907 that outdoor relief was too generous, that drink was the “main cause of pauperism” and she believed trade unions and the “feeble-minded” were too active. In the middle-class leafy suburb of Headingley, this was obviously a popular stance because she continued to be elected top or second the poll for many years. Both the Majority and Minority reports produced as a result of this Commission recommended the end of the workhouse system.

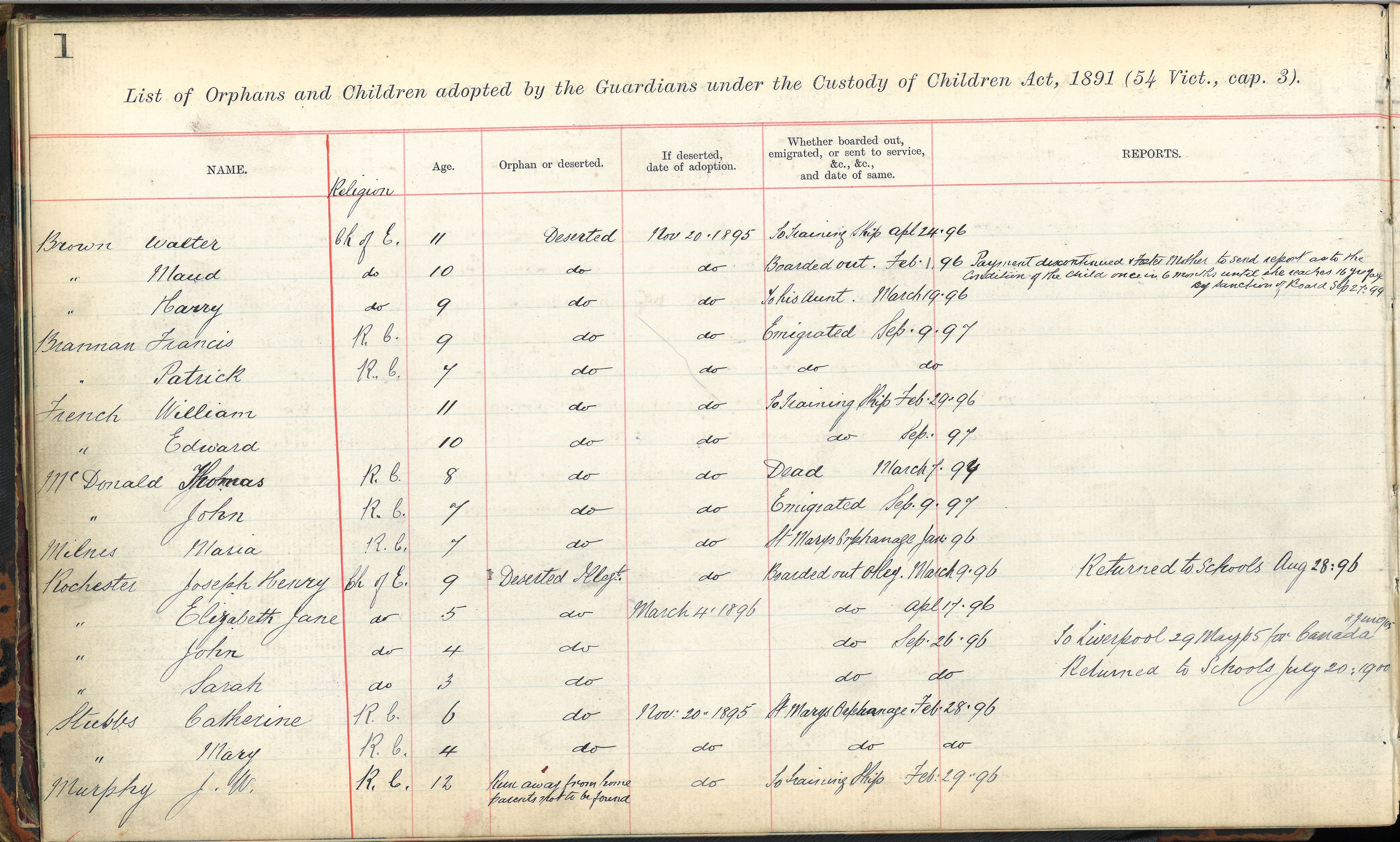

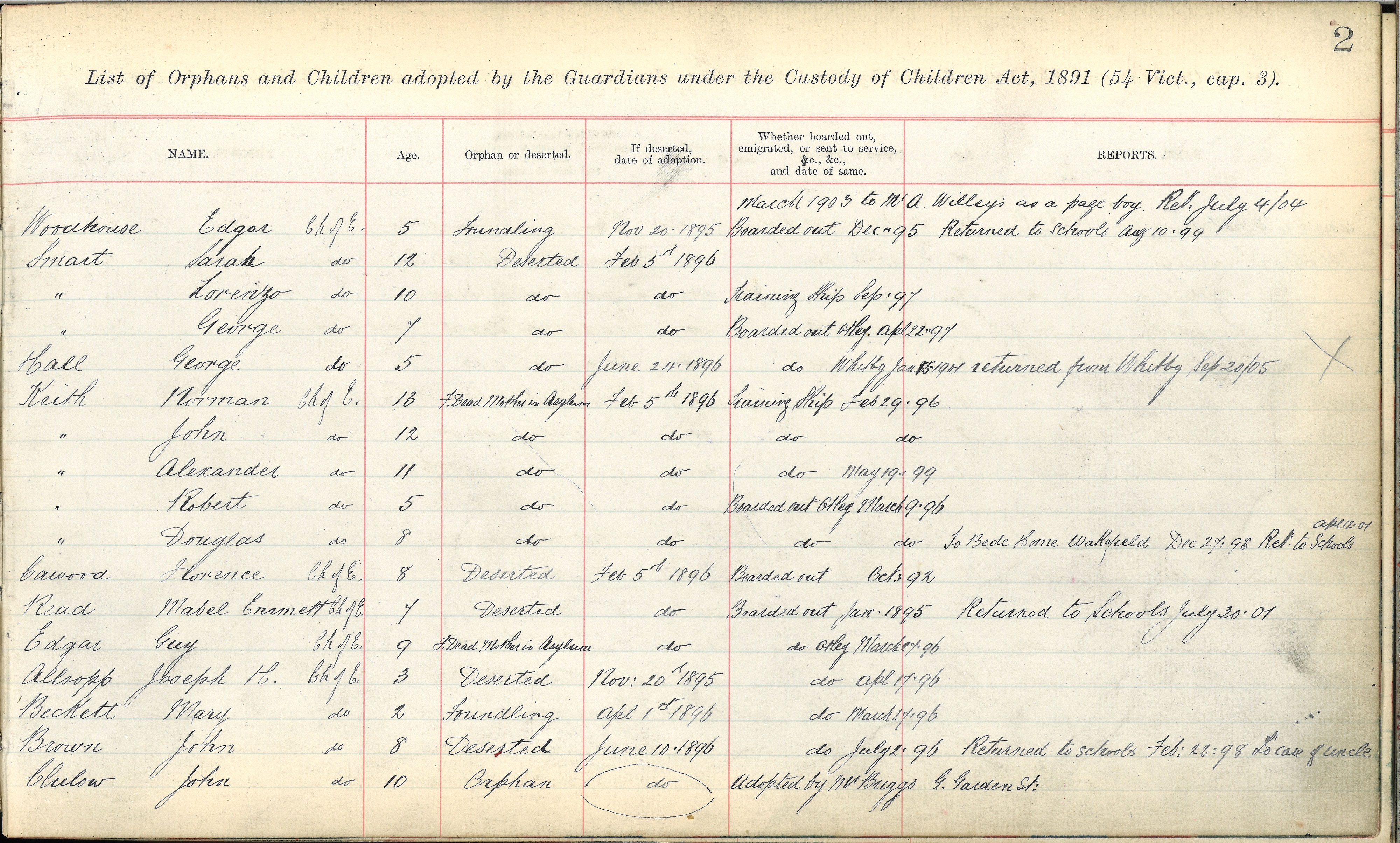

Margaret was responsible for introducing the “boarding out” or “scattered homes” system for pauper children in Leeds. The Poor Law Board were persuaded to purchase several ordinary houses around Leeds. A married couple were employed as foster parents to care for six or eight children. The children attended the local Board School and were integrated into the local community. This gave them a fresh start in life “removed from the taint of inherited pauperism.” In 1898, the Yorkshire Post reported the Guardians had eleven “scattered” homes, offering a “simple, free, natural and economical family life”. Miss Baines made a point of visiting on a regular basis. The foster mothers were expected to make the children’s clothes and were not allowed to use corporal punishment. Eventually the Board owned over a hundred such houses. They also purchased land on Street Lane, Roundhay: here they built a Central Home, where the children stayed during initial assessments, and an administrative centre.

Margaret Baines and her colleagues, especially Gertrude Wilson, gave papers and addressed conferences about the practicalities of administering the Poor Laws, and gave evidence to Parliamentary Select Committees. They became leading members the National Union of Women Workers with Women and Children. They wrote reports for and letters to the local newspapers, acknowledged as leaders in their field.

Unfortunately it has been impossible to trace any photographs or other images of them.

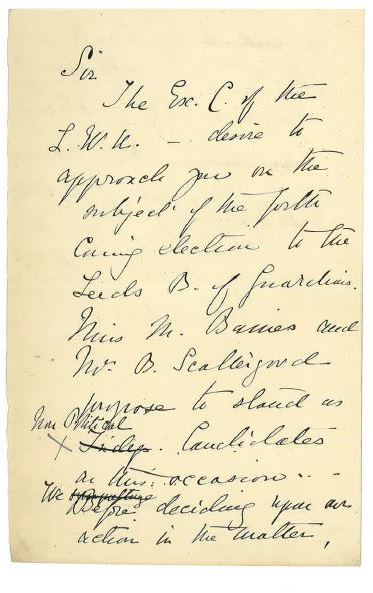

Canvassing Support from Political Parties

Sir

The Executive Committee of the Leeds Women’s Union – desire to approach you on the subject of the forth coming election to the Leeds Board of Guardians.

Miss M Baines and Mrs B Scattergood propose to stand as Non Political Candidates on this occasion

Before deciding upon an action in this matter, we beg to ask you whether you will consider the possibility of placing their names upon your list of candidates with the object of avoiding a contested election.

We are making the same enquiry of the C(ommittee) of the L(iberal) Association.

Undated letter, possibly addressed to the Leeds Conservative Party, from the archive of the Yorkshire Ladies Council of Education.

Image courtesy of West Yorkshire Archive Service

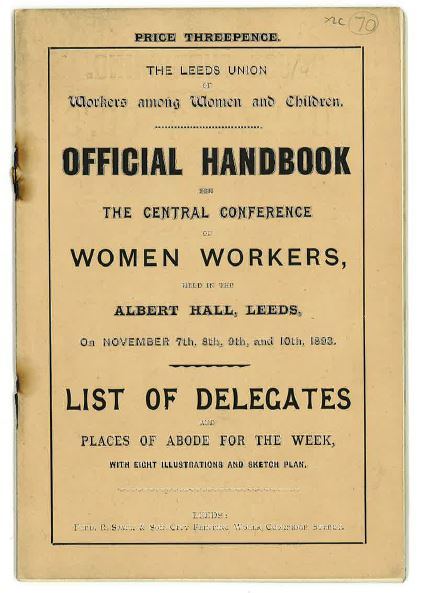

Handbook for the National Conference of Women Guardians and Women Workers among Women and Children

Held in Leeds 1893

Margaret Baines was involved in the organisation of this conference and one of the main speakers

CONFERENCE OF WOMEN WORKERS 1894

A paper was read on “Women as Factory Inspectors.” The proposed amendment to the Factory Acts, which gave the Home Secretary absolute power to decide what occupations and hours were fit for women, was calculated to injure women workers under the guise of beneficent legislation. Small laundries worked by women were to be crippled to drive the work to steam laundries worked by men. Miners were trying to get the women coal-pickers abolished. Women had been driven out of the bleaching trade and the same agitation was going on about women in lead works. If the government dared to turn tailors out of their employment because it injured their health, they would have to compensate them; but hundreds of respectable women had been deprived of their livelihood and driven into the workhouse.

A woman factory inspector maintained that it was suitable and desirable to open the higher grades of the Civil Service to women, and suggested changes in the department of inspectors. She found that women could speak more freely of their work to fellow women, and of what was needed to better their condition. The work of inspectors was however administrative and not legislative, but the present Factory Acts certainly required extension and alteration.

Miss Margaret Baines, who had a cordial reception, said that if one took the trouble to think at all as to whether women should be members of the Board of Guardians, it seemed so obvious that no argument was needed. In their everyday and home life women had the charge, almost the entire charge, of the children, of the sick, and of the old. Women, in all ranks of life, had a great deal to do with looking after the poor and destitute. Men could not do this, however much they might want to, because they had so little time; and if this charge was given to women in their everyday life it fitted them for the same charge anywhere. If they could deal with the twos and threes, they could also deal with the scores and hundreds.

As to the administration of the Poor Law, a very important consideration was when to give outdoor, and when indoor, relief. This matter ought to be attended to individually as much as possible, and by people who had time to go into each separate case. She should take a very great interest in the further classification of the inmates of the workhouse.

If possible, some arrangement should be made by which the respectable, honourable, poor should not be obliged to spend their lives in daily contact with evil influences and companionship, which it was now almost impossible for them to avoid.

One of the most hopeful parts of their work would be that relating to the children, whom she would like to be enabled to begin their lives without the brand of inherited pauperism on them, and to have a fair start and equal opportunity with other children.

Leeds Mercury 11 December 1894

reporting on ratepayers meetings before the first elections held under the Local Government Act

Photograph of “A Typical Family” in a scattered home for boarded out pauper children under the Leeds Poor Law Guardians, instigated by Margaret Baines and implemented from 1895

Image courtesy of Leeds Library & Information Service

Leeds Union Workhouse Chapel

Women in Public Life

It is to the credit of the women that they have succeeded in demonstrating their fitness to take an active part in helping forward political and social reforms.

The signs of the times all point in the direction of a wider sphere for intelligent and helpful women in our public life. The exclusive rule of the male sex on some, at least, of our public bodies is at an end. We have long accepted the presence of women on our School Boards and no one can say they have discharged their duties otherwise than creditably to themselves and with advantage to the community.

Now that the property qualification for members of Boards of Guardians have been removed, we are likely to see a number of women elected to those bodies because of qualifications more important than property.

On the Board of Guardians, there are at present two lady members as capable as any man, and one who is of more value than any ten of the men. They understand the whole scope of the duties of a Guardian, and are of inestimable service in dealing with women’s questions within and without the workhouse.

Two women will present themselves as candidates for the Leeds Board of Guardians at the coming elections in December and this testimony to the undoubted capacity of women to discharge duties hitherto discharged solely by men ought to be borne in mind.

Leeds Mercury 16 October 1894

Children's Homes in Leeds

There is an interesting article here from the Oakwood and District Historical society

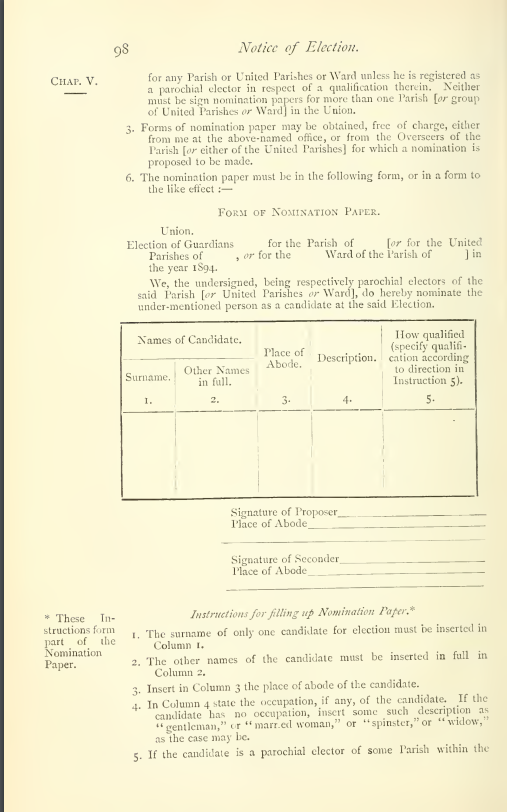

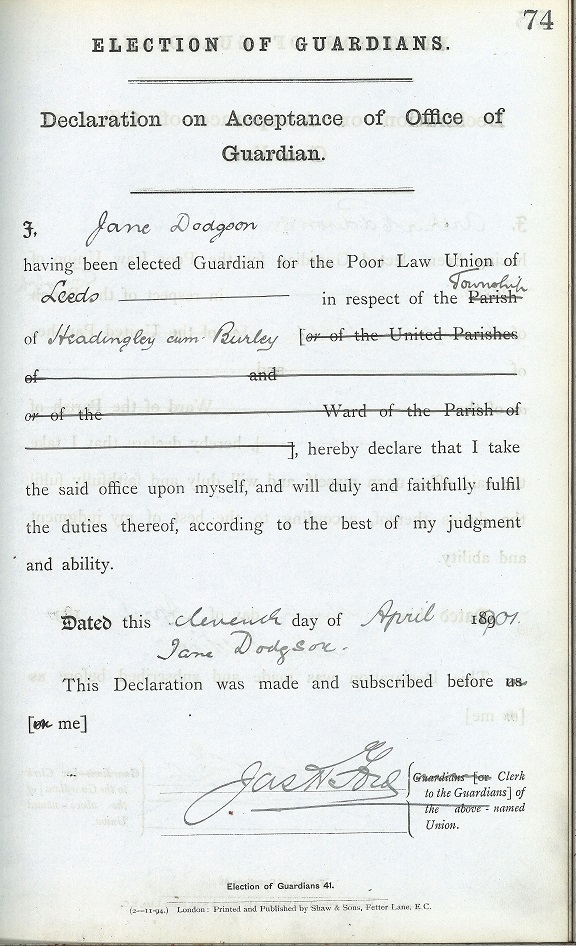

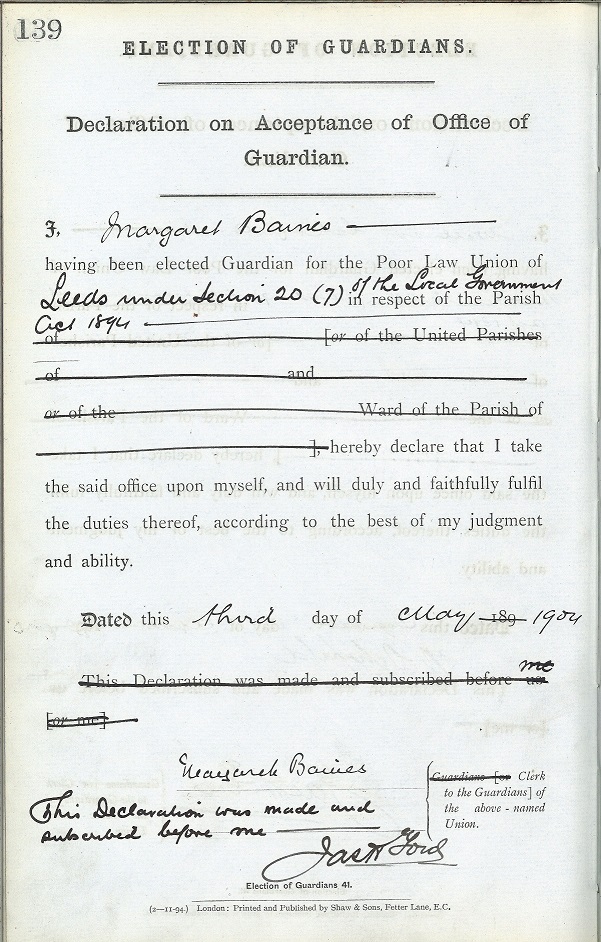

The Nomination Form for Poor Law Guardians

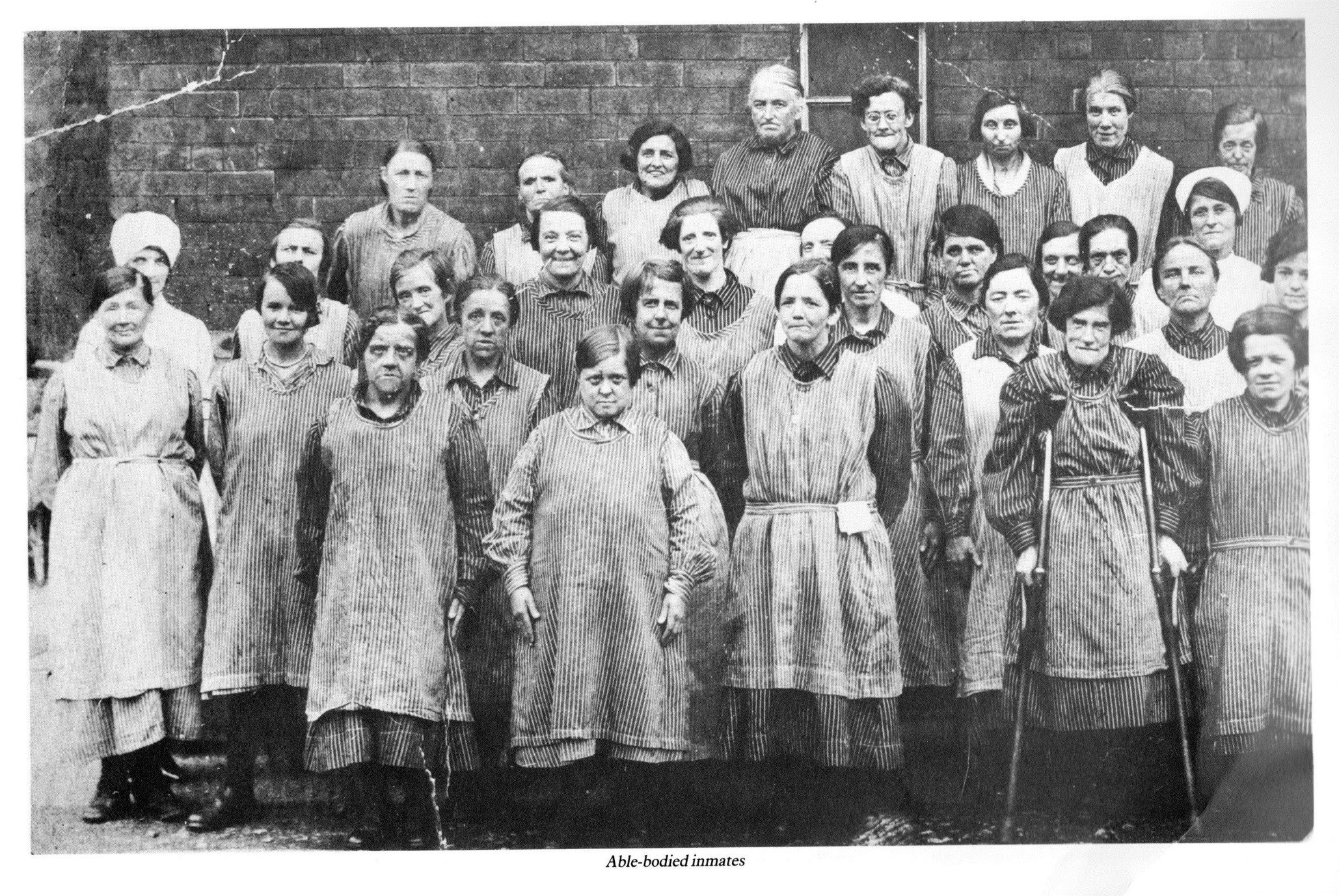

Women Inmates (Able-Bodied) of the Leeds Workhouse 1890s

Notice of Election as Poor Law Guardian

Junction of Woodbine Square and Woodbine Place, Little Woodhouse

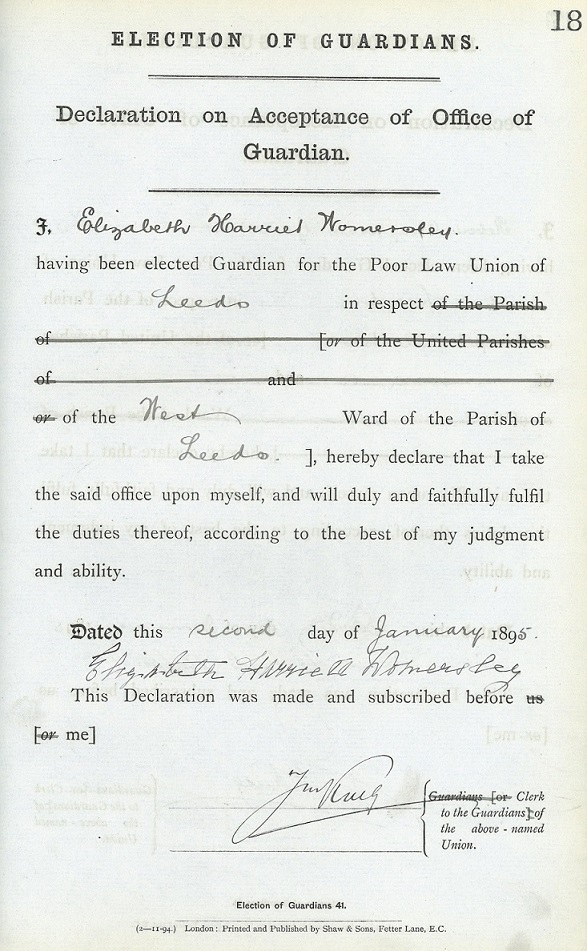

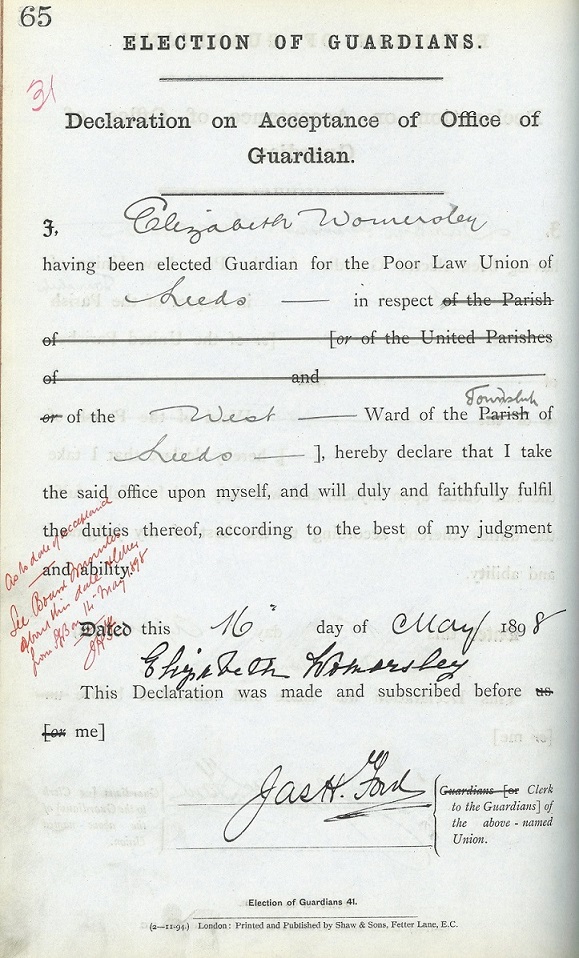

Mrs Elizabeth Harriett Womersley, who was elected as a Poor Law Guardian for the West Ward in 1894, lived on Woodbine Place.

She served two terms, from 1895-1897 and 1898-1900