Edith Pechey Phipson 1845 - 1907

“Everything was wanting except the patients”

Dr Edith Pechey

The First Woman Doctor in Yorkshire

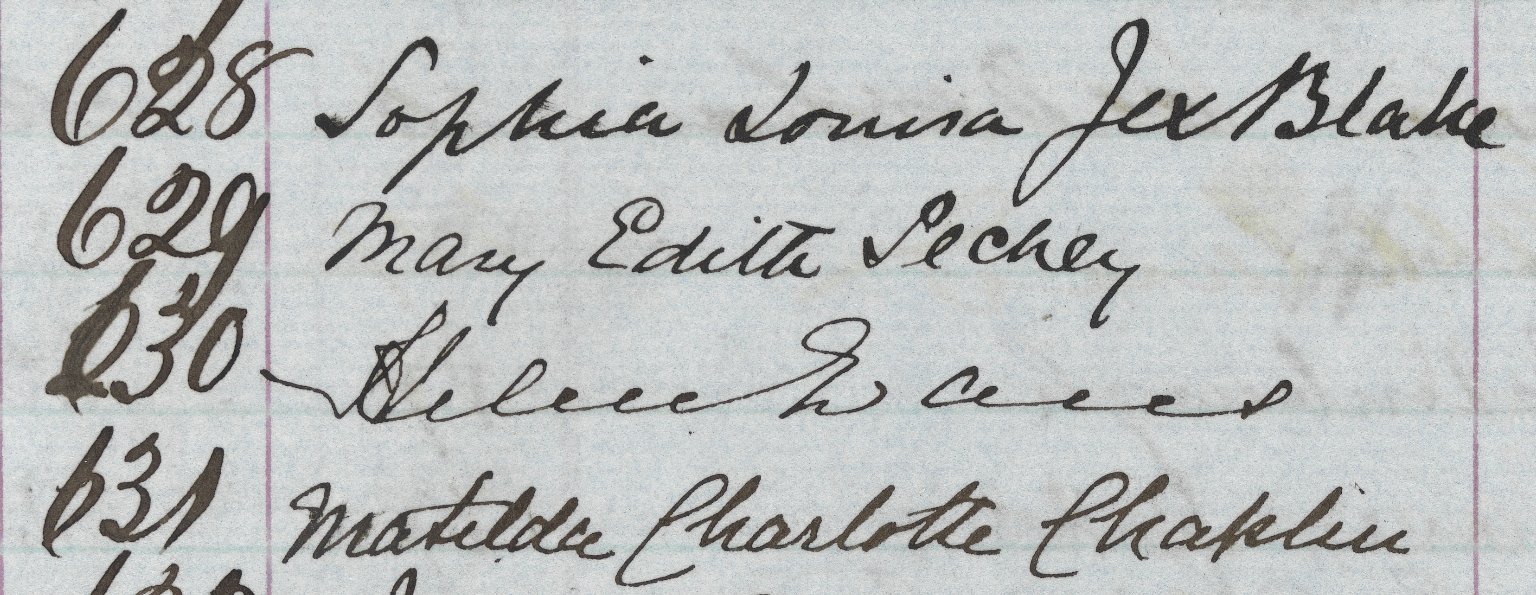

Sophia Jex Blake

Mary Andersen

Emily Bovell

Matilda Chaplin

Helen Evans

Edith Pechey

Isabel Thorne

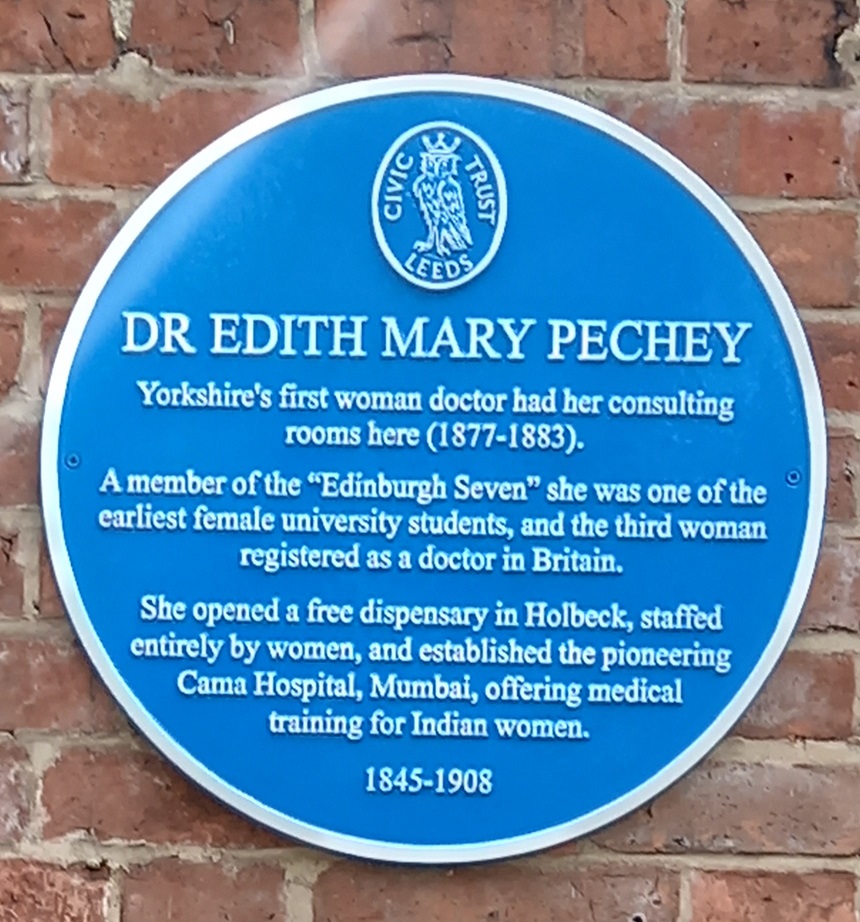

On International Women’s Day 2018 this plaque was unveiled in Edinburgh. It commemorates the first women to study at a British University, although they weren’t allowed to graduate. They wanted to study medicine so women patients might have the option to consult a female practitioner for specifically female health problems.

Edith Pechey was one of the "Edinburgh Seven" and she went on to become the first woman to practice medicine in England outside London when she opened her sugery in Leeds in 1877.

Early Years

Image courtesy of Ian Hollands, Langham Heritage Group

Mary Edith Pechey was born on 7 October 1845 in the village of Langham, near Colchester. She was the 6th child and 3rd daughter of William Pechey, a Baptist Minister and his wife Sarah.

Sarah was described as “competent in Greek and other subjects”, academic skills unusual enough then to provoke comment. William Pechey’s stipend was the family’s only income: enough to live on but little to spare.

There is no information about Edith’s early life but we may assume she and her sisters were educated at home. Edith recalled in a letter that she was interested in science, studying the butterflies and beetles as well as botany in the surrounding countryside.

All the Pechey children had to make their own way: two of her brothers emigrated aged only 16 to join an uncle as land surveyors in Australia. But the only respectable way for a middle-class lady to earn her own living was by her needle or by teaching girls and it is as a teacher that Edith first found herself in Leeds.

First stay in Leeds - Teaching

Image courtesy of Leeds Library & Information Services

Leeds in the 1860s must have come as a massive culture shock to 18 year old Edith, arriving from an agricultural village of less than 600 people. A visitor from less rural Cambridge wrote how he reeled in horror from the crowds and noise, the pall of smoke that obscured the sun, the dirt, the cheek-by-jowl extremes of wealth and poverty.

The local middle-class, made prosperous by these very conditions would have been insulted by his complaints about the “absence of art, literature and science.” They were proud of the fine Town Hall (opened by the Queen) and municipal buildings, the Mechanic’s Institute, the new Victoria Hall concert venue; all the great national associations to do with science, education and social improvement came to Leeds for their conferences.

This was the great age of professionalization. The sons of the merchants and mill owners in the Northern Towns were creating and exploiting new opportunities in engineering, science and technology. The established trades like medicine and law needed to protect their hard-won social status. So, over the century, professional bodies were established to register practitioners and control standards by erecting educational barriers to training which was standardised and regulated.

Women, the working class and other undesirables were thus systematically excluded.

So, the only profession left to middle class women who needed to earn a living was to teach small children and girls. But some women teachers believed they too deserved formal training and recognized qualifications together with the professional status thus conferred. They formed a campaign group and, in October 1867, they arranged a conference in Manchester on women’s education.

Sympathetic ladies from Leeds, Liverpool and Sheffield were invited to attend. These supporters agreed to form a Ladies Educational Association in each of these towns, to organise the university extension exams recently opened to women. Within a year, there were 12 such Educational Associations. Their umbrella organisation, under the unwieldy name of “the North of England Council for Promoting the Higher Education of Women” arranged lecture tours on subjects relevant to the exams.

The first lecture of the first series was held in Leeds. Was Edith one of the local teachers who attended? Her biographer says, “For a few years Edith taught school… she also had the experience of being a governess in a rather well-to-do household.” But the biographer provides no reference for this information.

These lectures offer a possible explanation of how Edith met Josephine Butler, the President of the North of England Council, who visited Leeds to attend that first lecture. Josephine Butler was publicly linked to the campaign for women doctors and Edith seems to have confided her ambitions to Mrs Butler.

Women in Medicine

The first British woman doctor was Elizabeth Garrett, (later Garrett Anderson) but, when she opened her London practice in 1865, she did so as a Licentiate of the Society of Apothecaries, a far less prestigious qualification. No medical school or training hospital would accept her and she only gained her Apothecary’s licence because her father threatened a law suit if she were prevented from sitting the final exam.

Elizabeth Garrett gained her training by exploiting loopholes in the existing system but, in every case, the loophole was swiftly closed after her to prevent others following her example. The campaigns to open both university education generally and the medical profession specifically to women developed simultaneously out of her struggle to qualify.

Reformers argued women doctors were needed because some women were prepared, quite literally, to die rather than discuss intimate symptoms with a male doctor. The prevailing belief was that, even in good health, women were weaker physically and mentally than men. In fact, the ideal 19th century woman might be characterised as an ignorant, silent, obedient, passive invalid. Alas, not many of those around, even then, and especially not in Yorkshire. Doctors insisted that any form of intellectual activity would irrevocably damage a woman’s reproductive organs and render her so ugly as to be unmarriage-able. No woman could be trusted with responsibility or decision making or money.

Of course, at the most basic level, doctors were protecting a lucrative part of their practice. Over the previous century, male doctors had encroached upon traditionally female medical skills, such as midwifery, to provide a reliable income stream BUT obstetrics, gynaecology and midwifery remained optional - not compulsory - subjects for medical students.

The Edinburgh Seven

Initial Application

Josephine Butler was in contact with Sophia Jex-Blake. Sophia was an independently wealthy young woman. She went to America to study medicine but was determined to practice in Britain. In April 1869, her application to Edinburgh University was rejected because it was “too difficult to make temporary arrangements in the interests of one lady.”

This was not a reference to the toilet facilities. Prevalent perceptions of what constituted “decency” meant the university authorities felt unable to provide mixed gender lectures in subjects such as anatomy or dissection. Indeed, soon after the Surgeons’ Hall Riot, a male supporter raised a laugh by suggesting the women medical students should be kept off hospital wards in deference to the delicate feelings of male students.

Sophia saw an opportunity in the wording of this particular rejection. She advertised in The Scotsman and The Times for other women applicants.

Josephine Butler wrote to her: “I saw a Miss Pechey at Leeds, who wishes to become a doctor. She did not seem to me very clever, but very steady and nice – a silent, quiet woman.”

Edith wrote to Sophia: “Before deciding finally to enter the medical profession, I should like to feel sure of success – not on my own account, but I feel that failure now would do harm to the cause…Do you think anything more is requisite to ensure success than moderate abilities and a good share of perseverance? I believe I may lay claim to these, together with a real love of the subjects of study.”

Sophia made a new joint application to Edinburgh for herself and six others. She agreed in advance to separate classes - which the women had to arrange for themselves with sympathetic male professors - and she agreed to guarantee whatever minimum fee the University might fix for these. The guarantee demanded was designed to deter: £100 per subject and each woman was charged 10 guineas per class (the male students paid only 4 guineas); this at a time when a female teacher might earn £30 a year. Edith was alarmed: “I am afraid I shall not be able to afford more than double the usual fees for a man,” she wrote to Sophia.

Studying at Edinburgh

copyright National Portrait Gallery

copyright National Portrait Gallery

To everyone’s amazement, the Medical Faculty and the University’s management committees agreed the women might sit the entry exam in October 1869. Sophia invited Edith to share a house in Edinburgh. She described her impressions of Edith to Josephine Butler: “I think her strong, ready-handed, with “faculty”, great ability, resolution, judgement; great calmness and quiet of manner and action, and probably strength of feeling; considerable sense of humour; lots of energy and interest in things – witness dissecting the slugs, keeping caterpillars etc. In fine, as good an ally and companion as could well be had.”

All the women applicants passed the entrance exam. Four of them were placed in the top seven of 152 candidates. The University had no choice but to enrol them. It was a decision which divided the male academic world. Many male students reacted aggressively, bursting into cacophonous laughter at the sight of the women, crowding into seats reserved for them and slamming doors in their faces. The situation became so bad that male students who supported the women formed an escort to see them safely to classes. Some, men and women, argued the women students brought the “unpleasantness” upon themselves.

The Surgeons Hall Riot

These pioneers faced vocal and very real physical opposition. In the most notorious incident, in November 1870, which this plaque commemorates, hundreds of male protesters barred the seven women students from entering the Edinburgh Surgeons’ Hall where they were due to sit an anatomy exam. The crowd was so rowdy that traffic came to a halt for over an hour. It was claimed at least two professors in the Medical School dismissed their classes early so the students could take part. When a (male) sympathiser unbolted the main door to the Hall so the women could enter, the protesters used a back entrance to shove a live sheep into the examination room. The crowd then mobbed the women as they left the Hall, chasing them through the streets, pelting them with stones, mud and rotting vegetation, shouting what Edith described as “all the foulest epithets in the voluminous language of abuse.” Police were notable by their absence. The Press described it as a “Riot”.

The Hope Scholarship

At the end of the first term, Edith gained the highest marks in Chemistry. This entitled her to the Hope Scholarship, £50 (around £5,000 today) plus free use of the University laboratory.

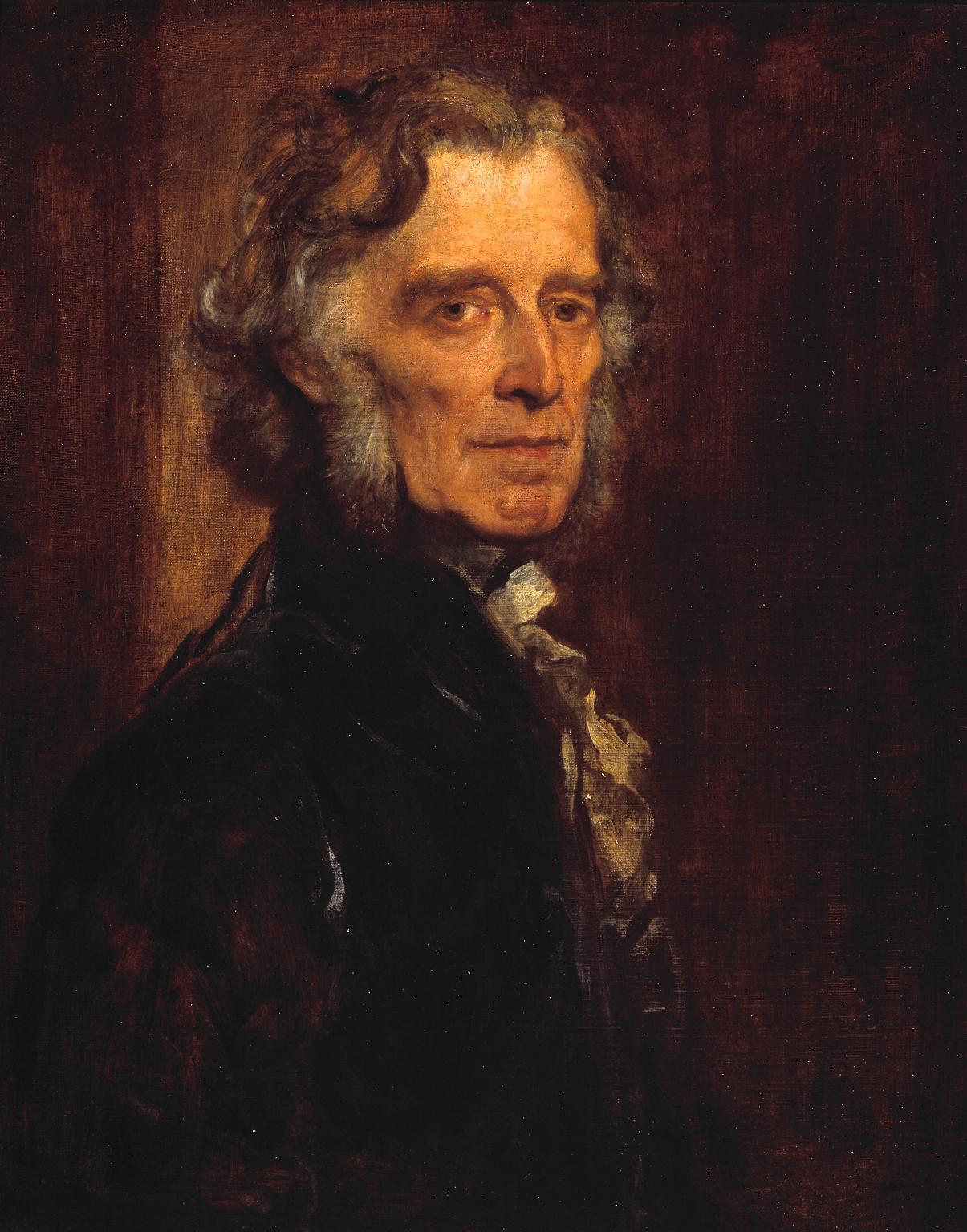

The Hope Scholarship had been established in 1826 by Thomas Hope, Professor of Medicine & Chemistry, from the profits of a series of public lectures which he allowed women to attend. A colleague complained:

“[He] lectures to ladies on Chemistry…He receives 300 of them and the ladies declare there was never anything so delightful as these chemical flirtations. I wish some of his experiments would blow him up.”

The Hope Scholarship fund paid an annual prize “to the most deserving student in the Chemical laboratory.”

Edith was denied the award by one vote because she had not attended the regular classes. As mandated by the University, she and the other women students were taught separately but by the same tutor. The awards panel did allow her to receive a medal for being among the top five students. The story was taken up by the national press.

Titus Salt junior (of Saltaire) wrote to The Times: “if the ladies did the same work, they were entitled to the same honour as students of the other sex. Her just and honourable claim I plead and, as there is in consequence a strong probability of her career being cut short, I appeal to those of my fellow men who feel that an injustice has been done to help me raise a fund to enable Miss Pechey to continue her studies.”

Edith declined his “most kind and chivalrous” offer but it began a friendship with the Salt family which supported her for many years.

Back in Leeds

Women and Girls Education

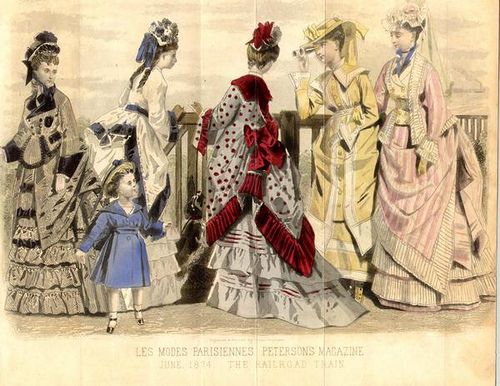

Soon after Edith left Leeds, the Yorkshire Board of Education formed a Ladies’ Council. Despite its misleading name, suggesting a statutory body, the Board of Education was actually a voluntary group. It established itself as an umbrella organisation for groups across the county interested in post-elementary education. Their Ladies Council was to implement educational initiatives for women.

The twelve Ladies Educational Associations and the Ladies Council all recruited their members from families enriched by local industry & manufacturing whose wives & daughters had the leisure to engage in “good works”. They tended to be Dissenters in religion and Liberals in politics. The Educational Associations were limited to their towns but the Ladies Council was able to invite members from across the whole county. Catherine Salt in Saltaire and her sisters-in-law, Martha and Jane Crossley from Halifax for example were all members. Membership often overlapped and the 2 groups co-operated on many projects, for example, opening the Yorkshire School of Cookery (1874) and in the campaigns for High Schools for Girls in Bradford, Leeds and Sheffield.

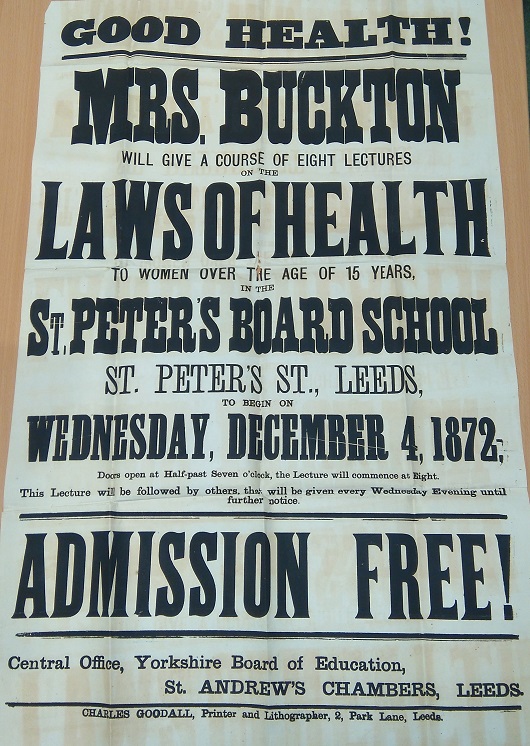

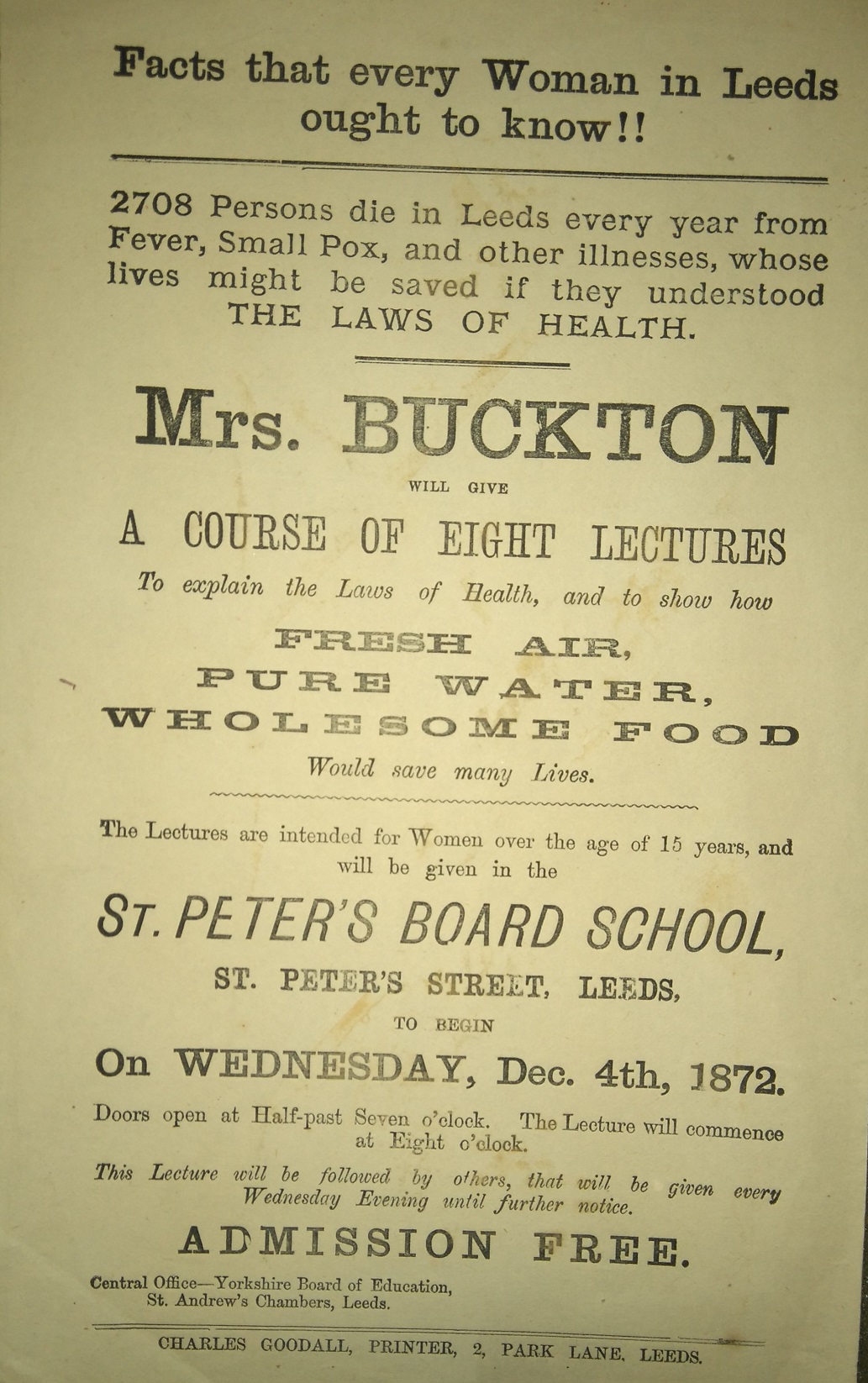

These women saw themselves as “enablers”. The great enemy was Ignorance; provide the necessary information (education) and people can choose to help themselves. The Ladies’ Council duly arranged “popular Lectures explanatory of the laws of health” for working-class women.

There had been concern about the state of sanitation and clean water provision in Leeds for a very long time. The Ladies’ Council believed “women of the industrial classes” should understand why cleanliness was important. Initially they engaged a professional male lecturer to address mixed audiences. A member, Emily Cliff Kitson, reported back: “I did not think these lectures were successful, nor did I think the subject was treated in such a manner as to be comprehended by the class of persons to be instructed.”

She drew up her own scheme. “Simple elementary teaching on sanitary matters should be given to women only…in the most densely populated parts of the town…in the form of Classes rather than Lectures, held once a week for not less than 6 consecutive weeks…illustrated by diagrams [and] conducted by a lady.”

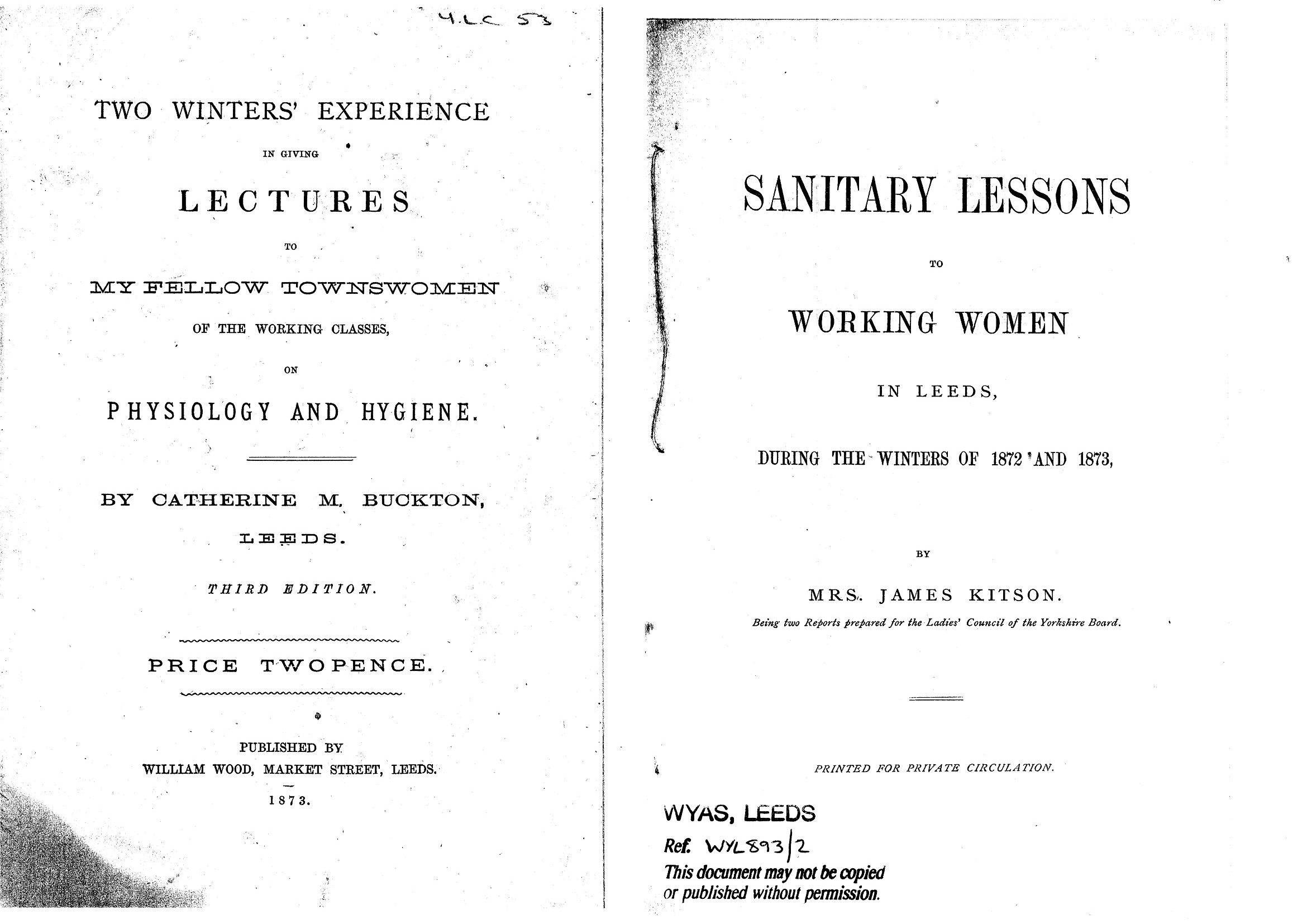

The new format classes proved popular. Attendance grew quickly. Within weeks, there were audiences of over a hundred women. Emily Cliff Kitson insisted on a maximum class size of 30 but her colleague, Catherine Buckton allowed as many as wanted to come. There was a talk for an hour then an informal discussion. Texts were lent for home study and there was a questionnaire to test understanding of each lesson. The Ladies’ Council purchased microscopes, anatomical models and diagrams and paid for prizes of books.

copyright Yorkshire Ladies Council of Education & West Yorkshire Archives Service

copyright Yorkshire Ladies Council of Education & West Yorkshire Archives Service

We know about these classes because both ladies reported back to the Council on their experiences. Mrs Buckton’s report was published at the affordable price of 2 pence and later she published all 25 lectures as a book “Health in the House”.

The lectures expanded beyond Leeds. Catherine Salt invited Mrs Buckton to lecture in Saltaire where the Bradford Observer reported audiences of over 500 women. The Leeds Ladies Educational Association invited Mrs Buckton to address the North of England Council at its annual conference in Leeds, and Queen Victoria’s daughter, Princess Alice of Hesse, wrote from Germany for details of their work. Other towns copied the idea.

Front pages of pamphlets describing the lectures to working women in 1872 and 1873, printed by the Ladies Council; Mrs Kitson’s was for private circulation; Mrs Buckton’s was offered for sale and went into 4 editions by the end of the year.

copyright Yorkshire Ladies Council of Education & West Yorkshire Archives Service

Goodbye to Edinburgh

A threat of legal action forced Edinburgh University to allow the women students to complete the classroom element of the medical degree course; this document shows their signatures in the matriculation register. To graduate, they now needed in-hospital experience. Edinburgh Infirmary refused them admission and the weary round of applications began again.

Edith wrote to Sophia after yet another rejection: “I have indeed suffered many things of many physicians, and my temper is no better…if only I could have spoken my mind when they talked their conceited bosh about their infinite superiority.”

Edith Returns to Leeds

Edith needed to earn some money. She obtained work at a maternity hospital in London during summer 1872 but her financial situation was becoming desperate. It was probably not coincidence that, in the November, Alice Cliff Scatcherd (Emily Cliff Kitson’s sister) suggested to the Leeds Ladies Educational Association that Edith be asked to “deliver a Course on Physiology” as part of their adult education programme. The audience paid 3 shillings to attend each lecture. Edith “expressed great pleasure in being invited to lecture… and [undertook] to deliver a course at the rate of 3 guineas a lecture and travelling expenses.”

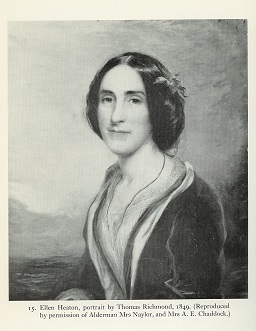

Ellen Heaton, sister of Dr John Heaton, intervened. There was a feeling amongst her acquaintances against engaging Miss Pechey, whose name was familiar to them from the Hope Scholarship controversy. The lectures, Miss Heaton believed, would not pay and she strongly objected to paying an untried lady lecturer on the same scale as men. But she failed to convince the Committee. They ordered 7,000 leaflets and placed adverts about the lectures in all the West Riding newspapers. A mere 6 weeks later, it was Miss Heaton who requested a further 250 leaflets.

Edith duly lectured in Leeds, York, Huddersfield and Halifax. Her audience averaged 135 and, unlike the other lectures in the series, they made a profit.

Edith was now approached by the Ladies’ Council to provide health lectures. Their Annual Report noted “the number of ladies attending the lectures and the interest manifested in them were highly satisfactory. A small surplus from the sale of tickets remained…this has been devoted to defraying the cost of conducting a simpler course for women of the industrial class [where] attendance averaged 200 each evening.”

The Ladies Council also noted: “The difficulty has been to find teachers not the taught.” Emily Cliff Kitson died of a childbirth related infection on 5 October 1873; and that November, Catherine Buckton became the first woman elected to public office in Leeds - as a member of the School Board. She resigned all her other public commitments to concentrate on her demanding new role. The Ladies Council needed Edith and more like her.

Catherine Buckton brokered a deal between the Leeds School Board and the Yorkshire School of Cookery to set up a course in Physiology leading to a teaching certificate. Edith helped her to design the syllabus; in a virtuous circle, the newly qualified teachers were then employed by School Boards throughout Yorkshire, the Ladies Council, the Leeds Ladies, and many other organisations.

A letter from Edith reveals that she requested a formal reference from the Ladies Council after offers to lecture in the South of England. The Editor of The Englishwoman’s Yearbook approached her for an article on lecturing as a possible field of employment for women. Edith’s reply indicates that she did not consider this a long-term option for herself: she still intended to find a way to complete her medical training.

Completing Medical Qualifications

Hospital boards nationally simply refused to open their wards to would-be women doctors. The only exception was the newly opened Birmingham & Midlands Hospital for Women & Children. They appointed Dr Louisa Atkins as Resident Medical Officer for 12 months. She had qualified at Zurich University but she was practicing unregistered and therefore illegally in Britain.

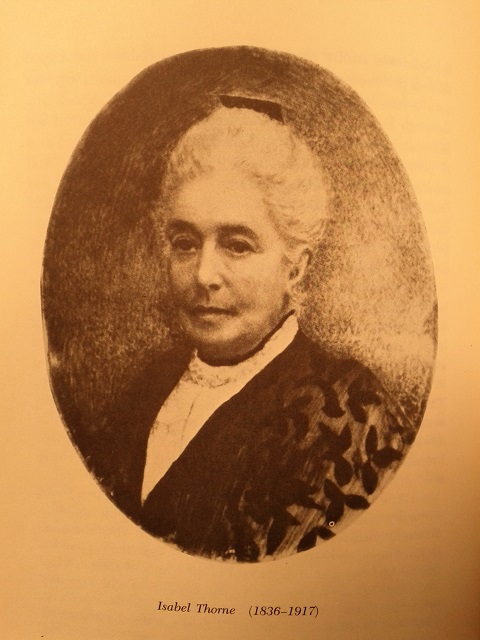

Sophia Jex-Blake and another of the Edinburgh Seven, Isabel Thorne, took action. They persuaded 14 supporters to invest £100 each as the working capital to open a medical training school for women doctors in London. It opened in September 1874 and Isabel Thorne gave up her medical ambitions to run it.

Dr Atkins’ term in Birmingham was so successful the Board determined to appoint another woman and offered the post to Edith. “It is impossible for her to qualify under existing procedures yet her certificates and testimonials give the fullest evidence of her competence. The Committee thinks itself singularly fortunate in securing the services of a lady of her distinguished attainments,” reads her testimonial.

Even while employed in Birmingham, Edith maintained contact with Leeds. In January 1875 she lectured on “The Physical Education of Girls”: “over 60 ladies attended in spite of exceptionally stormy weather.” That October she appeared at a networking event arranged by the Leeds Ladies and, in early 1876, she spoke at a public meeting in support of the projected High School for Girls. Nevertheless, as her tenure at Birmingham ended, she wrote to Sophia: “I suppose you can’t think of any way in which I can earn some money?”

We need to digress to national politics here. It had become obvious that only legislation was going to break the deadlock with the intransigent medical authorities. Despite huge opposition, after much negotiation and many compromises, Russell Gurney, a Conservative MP, steered a private member’s bill through Parliament.

The Medical Act 1876 allowed the British medical authorities to license female applicants with foreign medical degrees to practice in the UK.

The Englishwoman’s Review commented: the Act “was not passed on behalf of the few women who wish to obtain medical degrees but on behalf of the many women who wish to place themselves under medical advisers of their own sex.”

But it was only an “enabling” act: there was no compulsion to comply nor penalties for non-compliance and 18 of the 19 British medical authorities had no intention of complying.

King & Queen’s College of Physicians, now the Royal College of Physicians of Ireland, St Stephen’s Green, Dublin

The Board of King and Queen's College of Physicians, Dublin were at least prepared to consider the situation. Dublin was then the 2nd city in the UK. The Irish Board almost certainly took into account that the applicants, at least initially, were not Irish women and did not intend to practice in Ireland. No doubt, they also considered how the College might gain financially from the greatly enhanced fees it was allowed to charge the women applicants.

Sophia Jex-Blake paid for Edith to go to Dublin to plead their cause.

Edith persuaded the Board to recognize the London Medical School for Women as an accredited training centre and to licence women applicants who had foreign medical degrees.

Sophia reported jubilantly: “The success accomplished was due almost entirely to the excellent tact and judgement which Miss Pechey has, in Dublin, personally brought before the principal authorities concerned.”

Sophia and Edith enrolled at Berne University in Switzerland for the winter term. The lectures were given in German, the examinations had to be answered in German and their dissertations submitted in German, a language they had only started to learn 6 months previously.

Edith Pechey 1877, in her graduation robes – at last!

A portrait in the archives of The Medical Woman’s Federation in London, now the Wellcome Institute

First Medical Practice

Image courtesy of Leeds Library & Information Services

The obvious place for Edith to set up practice was, of course, Leeds. She was well known for her lectures and had the support of a widespread network of influential, wealthy ladies, among whom she might hope to find her paying patients. In modern parlance, she could hit the ground running.

Edith took lodgings at Warwick Villas, 20 Coventry Place in Leeds - ironically on the same street as the Women & Children’s Hospital who would neither employ her nor accept patients referred by her.

Edith’s consulting rooms needed to be in the centre of town so she took an office suite at the impressive 8 Park Square.

It was a point of principle for the early women doctors to charge the same fees as their male colleagues. To do otherwise was an admission that their work was worth less than a man’s.

As the number of women entering medicine increased, they felt the need for the same sort of networking professional body enjoyed by male doctors. In 1878, the British Medical Association voted against admitting any further women members so Elizabeth Garrett Anderson remained the only woman member until 1892. So the women doctors created their own equivalent organisation, the Association of Registered Medical Women, later The Medical Woman's Federation. In 1882, Edith was elected President.

Mill Street

Image courtesy of Leeds Library & Information Services

Edith Pechey was the only woman doctor in the North of England. Elizabeth Garrett Anderson, based in London, was consulted by women as far afield as Manchester and Newcastle. It is reasonable to assume Edith’s practice was equally extensive. Mrs Hannah Ford of Adel and her daughters, Emily and Isabella were among Edith’s patients so it is probable that Edith was consulted by other members of the Leeds Ladies Educational Association and the Ladies Council (now known as the Yorkshire Ladies Council of Education). She continued to lecture for them across Yorkshire, frequently giving her time pro-bono to provide free talks for working-class women which were “crowded to over-flowing.”

The male medical establishment in Leeds refused to allow Edith to work at the Public Dispensary, which provided the only free healthcare in the town. So, in 1881, she set up a Dispensary for Women & Children in Mill Street, Holbeck, one of the most deprived slum areas in Leeds. It was funded by donation and staffed entirely by women.

She also assisted the Yorkshire Ladies Council to establish a Trained Nurses Institute in Leeds. Invalid ladies were, of course, cared for at home not in a public hospital and minor operations were routinely carried out in the home. The Institute employed nurses trained in the new Nightingale schools. The profits from private nursing fees provided free Nurses and Midwives to work in slum districts. The Nurses from the Institute and other local hospitals benefited from free entry to Edith’s lectures while Edith recommended the Institute to her paying patients and worked alongside the free District Nurses.

Edith appointed Dr Alice Ker as the Medical Officer at her Dispensary. Alice’s family, the Stevensons, were influential supporters of the Edinburgh Seven so Alice and one of her cousins, Agnes McLaren were among the second wave of women doctors to qualify. After completing her studies at the London School of Medicine for Women, Alice followed Edith as Resident House Surgeon in Birmingham before coming to Leeds. She wrote in her diary that Edith introduced her to “many interesting and distinguished friends” in Yorkshire.

Hill House, Bramley Top

Image courtesy of Leeds Library & Information Services

Edith’s practice was successful enough for her to move out of urban Leeds to the rural surroundings of Bramley Top. She took three months leave during the winter of 1879/1880 to enjoy a Nile cruise. This provided material for an article on “Egypt as a Winter Residence for Invalids.”

India

The Cama & Albless Women and Children’s Hospital in Mumbai, opened in 1886. Edith Pechey was Senior Medical Officer from 1884 to 1905.The Hospital still exists.

In 1883, while in Vienna to obtain more surgical experience, Edith was approached by the Medical Women for India Society. They wanted to set up a hospital in India for women prohibited by religion from consulting male doctors. The Cama Hospital in India was to be staffed solely by women and would provide training for Indian women to qualify as doctors and nurses. In 1890, their first student came to Britain to complete her studies at the London Medical School for Women.

Edith accepted the offer and sold her practice to Alice Ker. Alice returned to Edinburgh after only 2 years. She sold the practice to Dr Ursula Chaplin who moved her consulting rooms to Woodhouse Square. By 1906, Dr Chaplin needed to take on a partner.

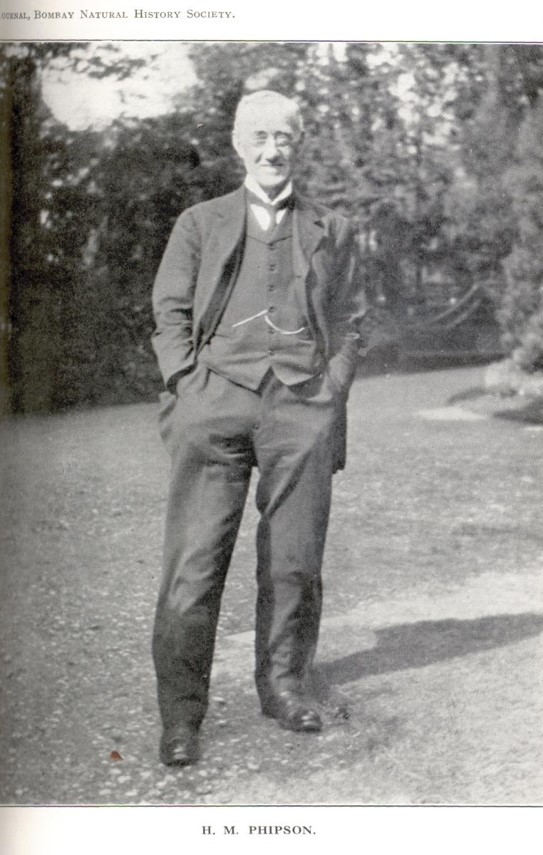

Herbert Phipson, 1850-1936 Wine Merchant and Naturalist

Editor of The Bombay Natural History Society Journal

Soon after her arrival in India, Edith met Herbert Phipson, a wine merchant based in Bombay. His offices were also the headquarters of the Natural History Society so his customers could browse the Society’s Library and Museum while choosing their wines. Edith and Herbert married in March 1889. Together they opened the Pechey-Phipson Sanatorium, a convalescent community for working women, at his summer estate of Nasik, north of Bombay.

Suffrage Work in England

The International Woman Suffrage Alliance

Banner and Commemorative Plate

Although Edith’s correspondence has been lost, she obviously maintained friendships in Yorkshire. We know she returned to England on leave in 1891 and 1896 because, on both occasions, she read a paper at a meeting of the Association of Registered Medical Women.

I’m sure you’re not surprised to learn she supported the women’s suffrage campaign. In 1881, she addressed the Women’s Grand Suffrage Demonstration in Bradford, organised by Alice Cliff Scatcherd of Morley; and we know that Alice and her husband visited Edith in India in 1896. In Alice’s scrapbook in the Morley Library is a letter in which she describes accompanying Edith on home visits to her patients.

Edith also kept in touch with Isabella Ford and her sisters in Adel. They were the mainstays of the Leeds Women’s Suffrage Society. When the Phipsons retired to England in 1906, Edith was appointed as the Leeds delegate to an International Women’s Suffrage Alliance Conference in Copenhagen. She visited Leeds that October to make her report.

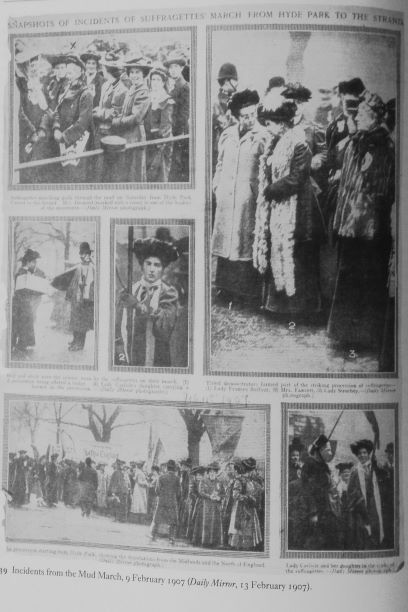

The Headline is "Snapshots of Incidents of Suffragettes March From Hyde Park to the Strand"

Mud March Titled Ladies

The caption is "Titled demonstrators formed part of the striking procession of Suffragettes

(1)Lady Frances Balfour, (2) Mrs. Fawcett, (3) Lady Strachey"

We think Edith is in the hat, immediately behind Lady Strachey

Edith represented the Leeds Society again at the first of the Woman’s Suffrage processions in February 1907. It was organised by the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies and nicknamed the “Mud March” because of the foul weather. Despite being seriously ill and in pain, Edith marched at the head of the procession with Millicent Garrett Fawcett, President of the Union.

Final Years

The next year Edith underwent surgery for breast cancer. The surgeon was Dr May Thorne, daughter of Isabel Thorne of the original Edinburgh Seven. The surgery was unable to halt the progress of the disease and Edith died on 14 April 1907.

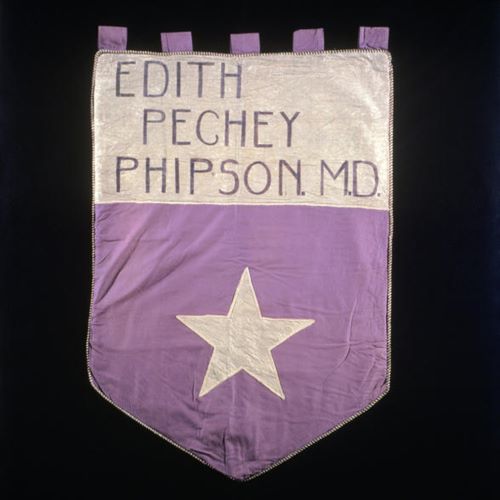

In 1908 the NUWSS marched under banners created to honour great women; this one commemorated Edith.

In July 2021 a plaque was unveiled at the site of Edith's first consulting rooms in Park Square, Leeds. The plaque was unveiled by Vine Pemberton Joss.